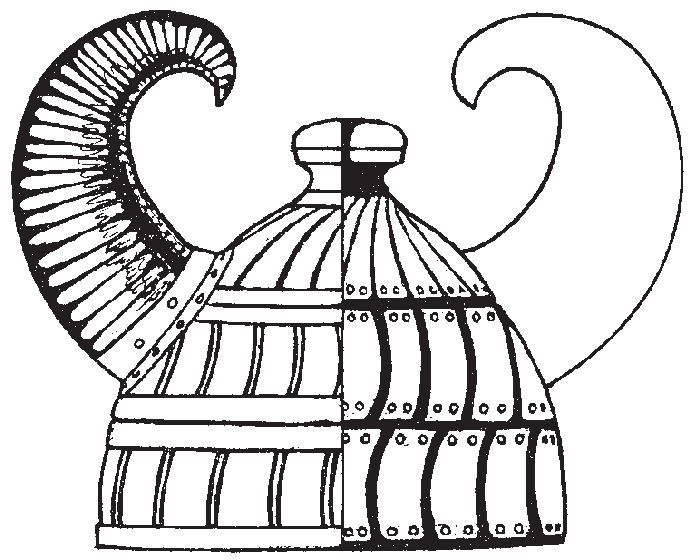

3,500-Year-Old Mycenaean Boar Tusk Helmets: that headline has been making the rounds across history journals, museum newsletters, and archaeology departments, and for good reason. This discovery isn’t just another ancient object pulled from the ground. It gives historians rare, physical confirmation of how people lived, fought, and told stories more than three millennia ago.

As someone who has worked with cultural heritage publications and archaeological interpretation, I can tell you plainly: most artifacts teach us something small — diet, trade routes, pottery styles. But once in a while a discovery changes interpretation itself. That’s what these helmets do. They help connect ancient literature, oral tradition, warfare studies, and material science into one real-world example you can actually hold in your hands. The helmets were discovered near Pylos in southwestern Greece, a known stronghold of the Mycenaean civilization (about 1600–1200 BC). This civilization existed roughly 500 years before classical Greece, meaning before Socrates, before democracy in Athens, and even before most Greek temples were built.

Table of Contents

3,500-Year-Old Mycenaean Boar Tusk Helmets

The discovery of the 3,500-year-old Mycenaean boar tusk helmets near Pylos is not simply an archaeological curiosity. It provides tangible proof of elite Bronze-Age warrior culture, confirms descriptions in ancient epics, and demonstrates that oral storytelling can preserve accurate historical memory across centuries. For scholars, teachers, and everyday readers, the helmets offer a rare bridge between myth and measurable evidence — reminding us history often survives long before formal records.

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| Discovery Location | Pylos, Greece |

| Age | About 3,500 years old |

| Civilization | Mycenaean Bronze Age |

| Armor Type | Boar tusk composite helmet |

| Estimated Boars Used | 40–50 animals per helmet |

| Literary Connection | Described in Homer’s Iliad |

| Social Status | Elite warrior / ruling class |

| Military Importance | Early organized warfare evidence |

| Official Academic Resource | https://www.ascsa.edu.gr |

Understanding the Mycenaean Civilization

Before we even talk helmets, you need a clear picture of who the Mycenaeans were.

The Mycenaeans were the first advanced Greek-speaking civilization in Europe. They built fortified cities surrounded by massive stone walls so large later Greeks believed giants must have built them. Today archaeologists call that architecture Cyclopean masonry because the stones were so big people assumed only mythical Cyclopes could move them.

They controlled trade routes across the Mediterranean. Archaeologists have found Mycenaean pottery in:

- Egypt

- Turkey

- Cyprus

- Italy

This tells professionals something important: they were not isolated tribes. They were a networked economic power — essentially a Bronze-Age trade empire.

At Pylos, archaeologists discovered clay tablets written in a script called Linear B, which scholars later deciphered. Those tablets recorded:

- livestock counts

- tax collection

- weapon distribution

- troop mobilization

That means the Mycenaeans had record-keeping bureaucracy similar to early governments. So when elite armor shows up in a burial site there, historians recognize it as part of an organized military system, not a random warrior burial.

What Makes a 3,500-Year-Old Mycenaean Boar Tusk Helmets Special?

The boar’s tusk helmet was not just protective gear — it was a technological solution to a Bronze-Age problem.

Metalworking existed, but bronze was expensive and heavy. Early full metal helmets were uncomfortable and hot. Warriors needed something lighter but still protective.

The solution was what we would now call composite armor.

Here’s how they made one:

- A leather skullcap base was prepared.

- Hunters collected boar tusks.

- Tusks were cut into thin curved plates.

- Plates were polished smooth.

- Each plate was drilled and sewn in overlapping rows.

That overlapping structure worked similar to modern ballistic plating — blows were deflected rather than absorbed.

The science matters. Boar tusk is a type of dentin, a material stronger than bone but lighter than bronze. When layered, it spreads impact energy. For an ancient warrior, that could be the difference between a concussion and survival.

Why Only Elite Warriors Owned Them?

A single helmet required tusks from around 40–50 wild boars. Hunting one boar was dangerous. These animals can weigh over 200 pounds and charge at high speed. Without firearms, hunters relied on spears and teamwork.

So the helmet wasn’t just armor. It was proof of:

- wealth

- social rank

- leadership

- hunting success

Anthropologists call this a status object. In American terms, imagine a decorated military officer’s ceremonial uniform combined with a custom tactical helmet.

Archaeological research shows such helmets were often buried with high-ranking individuals — likely chieftains, commanders, or noble warriors.

Connection to Ancient Literature

Here’s the part that has scholars especially excited.

In the epic poem Iliad, written around the 8th century BC, a character is described wearing a helmet covered in white boar tusks stitched onto leather. For decades historians argued:

Was that poetic imagination?

Or a real object remembered through oral storytelling?

Now archaeology answers that question. The helmets match the literary description.

This matters academically because the Iliad was written roughly 500 years after the Mycenaean period. That means oral storytelling preserved accurate details across centuries.

For cultural historians, that’s groundbreaking. It shows oral tradition — similar to Indigenous storytelling traditions around the world — can carry factual historical information far longer than previously assumed.

The Military System of the Mycenaeans

The helmets also help reconstruct warfare.

Evidence from Pylos tablets indicates organized troops. Mycenaean armies used:

- spears

- long shields

- chariots

- body armor

Chariots were especially important. Unlike later cavalry, they functioned like mobile command vehicles. Leaders directed troops from them.

The helmet therefore likely identified commanders. In combat, recognition mattered. Soldiers needed to see leadership across the battlefield.

Modern military historians compare this to identifiable officer insignia today.

How Archaeologists Study the 3,500-Year-Old Mycenaean Boar Tusk Helmets?

When archaeologists excavate a site, the helmet does not appear intact like a museum piece. Instead they find fragments.

Here’s the process professionals follow:

Excavation:

Careful soil removal using brushes and dental tools.

Documentation:

Every fragment mapped and photographed in place.

Conservation:

Organic materials stabilized immediately. Exposure to air can destroy ancient material.

Analysis:

Scientists perform radiocarbon dating and microscopic wear analysis.

Reconstruction:

Fragments matched using curvature patterns and stitching holes.

Without this process, artifacts could crumble within hours of discovery.

Why 3,500-Year-Old Mycenaean Boar Tusk Helmets Discovery Matters for Modern Education?

For teachers and curriculum planners, this discovery shifts how ancient history is taught.

Previously:

Myths and epics were often separated from real history.

Now:

We know literature preserved material culture details.

This influences:

- world history education

- literature interpretation

- anthropology

- cultural studies

For students, it teaches an important lesson — historical truth isn’t always only in written records. Sometimes it survives in stories.

Broader Cultural Meaning

The helmets reveal something deeply human: people have always linked identity to storytelling and symbols.

In Mycenaean society:

warrior = leader

hunter = provider

helmet = honor

Modern society isn’t that different. Military decorations, police badges, and even sports team gear serve similar symbolic roles. They communicate belonging and achievement.

Practical Insights for Professionals

For historians:

Combine archaeology with literature analysis.

For museum curators:

Artifacts should be interpreted alongside oral traditions.

For writers and educators:

Ancient texts may preserve real historical observations.

For archaeologists:

Material culture can validate literary sources.

Archaeologists Discover a Rare Lead Pipeline in Petra’s Ancient Aqueduct

Scientists Recreate the Scents Used in Ancient Egyptian Mummification

Perfect Bronze Age Sword Discovery Reveals Secrets Of Ancient Craftsmanship