Ancient Mariners Reached the High Arctic 4,500 Years Ago: this isn’t just a catchy headline. It’s a game-changing revelation from archaeologists who discovered that long before modern technology existed, Indigenous mariners had already mastered long-distance sea travel across some of the most treacherous waters on Earth. The idea that people living 4,500 years ago — known as Paleo-Inuit — navigated through icy Arctic seas, reaching the remote Kitsissut Islands (also called Carey Islands) off Greenland, challenges everything many thought they knew about ancient Arctic life. These early mariners didn’t just survive; they thrived by planning voyages, building sea-worthy boats, and returning seasonally to exploit rich marine environments.

Table of Contents

Ancient Mariners Reached the High Arctic

This discovery — that ancient mariners reached the High Arctic 4,500 years ago — flips the script on how we understand Arctic history. The people who made these journeys weren’t simply surviving; they were thriving, innovating, and navigating some of the most dangerous waters on Earth with skill and confidence. These ancient Arctic navigators were, in every way, engineers of their world. Their story is not just about the past — it teaches us how knowledge, resilience, and respect for the environment can guide humanity forward.

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| Discovery | Evidence of Arctic island sea crossings 4,500 years ago |

| Group Involved | Early Paleo-Inuit seafarers |

| Main Site | Kitsissut (Carey) Islands, northwest Greenland |

| Distance Traveled | ~53 km (33 miles) across open ocean |

| Vessel Type | Wood-framed, skin-covered boats similar to early kayaks |

| Archaeological Finds | 300+ stone features: tent rings, hearths, tools |

| Significance | Challenges previous models of prehistoric land-based Arctic migration |

| Published In | Antiquity – Peer-reviewed archaeology journal |

| Official Source | https://www.antiquity.ac.uk |

The Forgotten Mariners of the North: Ancient Mariners Reached the High Arctic

Mainstream archaeology has long focused on large ancient civilizations like Egypt, Mesopotamia, or Greece. But what if some of the most advanced navigators in early history were Indigenous Arctic people who paddled across open seas with nothing more than animal-skin boats and ancestral wisdom?

The new research highlights that ancient Arctic communities were not bound to land as once thought. Instead, they made seasonal open-water journeys to remote islands to hunt, gather, and thrive, using tools, technology, and planning that matched their environment.

Repeated Journeys, Not One-Off Trips

Archaeologists documented over 300 distinct features on these islands — including:

- Stone rings that held down the edges of skin tents

- Charcoal hearths used for warmth and cooking

- Animal bones from seabirds, fish, and possibly marine mammals

These aren’t signs of a single journey. They point to multi-generational seasonal use. People were returning again and again, passing down knowledge like wind patterns, celestial navigation, and sea behavior — long before compasses were ever invented.

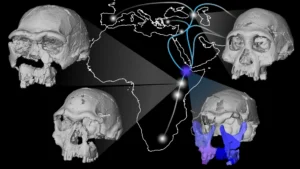

Who Were the Paleo-Inuit?

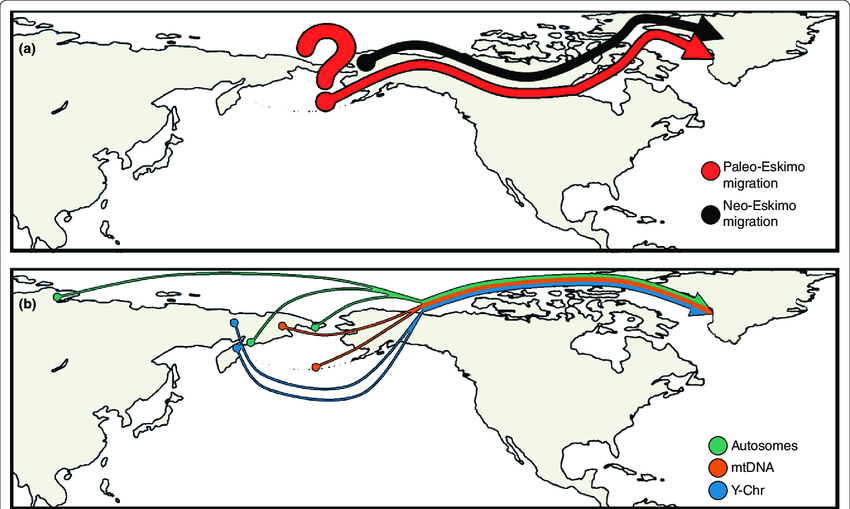

The Paleo-Inuit, also known as the Early Arctic Small Tool tradition, lived in the Canadian High Arctic and Greenland thousands of years before the Thule or modern Inuit. These ancestors built small, portable dwellings, crafted delicate flint tools, and most notably, appear to have been early seafarers.

What makes this discovery powerful is how it brings voice to ancient cultures that have often been overlooked or misrepresented in global archaeology. The old assumption was: if people were in the Arctic, they stayed on land, followed herds, and feared the sea.

But as the evidence shows — they embraced the sea. They knew it, read it, and used it to expand their reach.

Building and Using Boats Without Metal

Let’s not underestimate what this group accomplished. Crossing the 53 km of open water to the Carey Islands meant:

- No metal nails

- No navigation instruments

- No motorized aid

- Thick fog, unpredictable currents, strong winds

They did it anyway.

Their boats were likely constructed from driftwood or bone frames, covered in stretched sealskin and sealed with natural oils or sinew lashings. Lightweight, flexible, and fast — these watercraft resemble modern Inuit kayaks and umiaks.

This wasn’t just functional design — it was Indigenous engineering shaped over generations of careful testing and refining.

Ancient Mariners Reached the High Arctic: Navigating Without a Compass

Ancient Arctic mariners didn’t use maps or compasses. Instead, they relied on:

- Celestial knowledge: tracking stars and sun angles

- Weather cues: reading wind direction and wave formation

- Ecological patterns: like bird migration, animal behavior, and cloud reflections off ice

- Shared oral knowledge: storytelling from elders embedded direction, distances, and dangers

That last point? That’s how Indigenous navigation still works in many cultures today — not written, but remembered and lived.

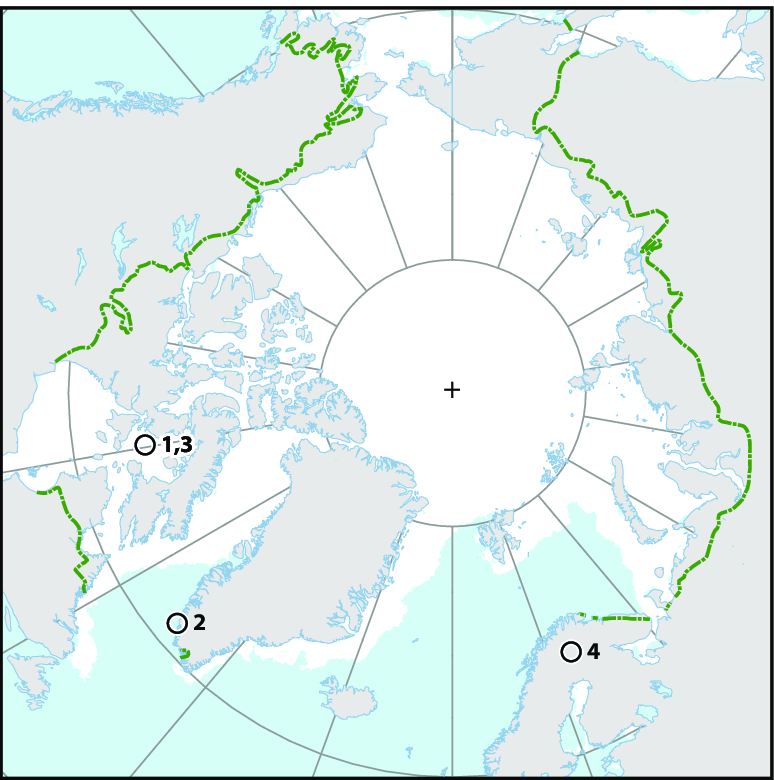

Why Did They Go to the Islands?

So why make the trip?

The Kitsissut Islands are located near a polynya — an area of open water surrounded by sea ice that stays navigable during warmer months. These polynyas are biodiversity hotspots, drawing:

- Seabird colonies (great for egg gathering)

- Seals and fish

- Driftwood, useful for fuel and building

They were like natural Arctic supermarkets — but you had to know how to reach them and when to go. And the Paleo-Inuit knew both.

New Tools of Archaeology

The study — published in the Antiquity journal — didn’t just stumble on the site. It used modern tools like:

- Radiocarbon dating of bones to age the sites

- Geographic mapping to understand travel routes

- Ethnohistorical comparisons with later Inuit traditions

- High-resolution satellite imagery to spot sites from space

This is a blending of Indigenous knowledge with Western science, and it’s producing powerful new understandings of history.

Rewriting the Textbooks

For generations, schoolbooks taught that Arctic peoples mostly walked across land bridges or hugged coastlines. This study shows that open-sea navigation was not just possible — it was practiced.

It also proves that advanced human migration didn’t just occur in warm, “civilized” regions. Innovation, collaboration, and survival skills existed wherever people lived — even on the edge of the polar ice.

This has big implications for:

- Archaeology

- Marine anthropology

- Climate adaptation studies

- Indigenous rights and history

Cultural Significance Today

This isn’t just a cool historical fact. For modern Inuit and Indigenous Arctic communities, this kind of research validates traditional knowledge systems that Western science has ignored for years.

It supports the belief that Indigenous peoples didn’t just adapt to the Arctic — they helped shape it.

As Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the Canadian Inuit organization, states: “Our ancestors were engineers, navigators, and scientists.” And now, the evidence is backing that up more than ever.

Educational Takeaways

Educators, parents, and students can use this study to:

- Highlight Indigenous innovation in STEM topics

- Compare Arctic travel to Polynesian voyaging

- Build lessons around climate, ecology, and adaptation

- Use oral history in classroom discussions

This story can inspire culturally responsive education, showing that science isn’t always about lab coats — it’s also about listening, observing, and living with the land.

Scientists Recreate the Scents Used in Ancient Egyptian Mummification

Atlantis Revisited — What Science Says Versus the Ancient Mystical Accounts

Ancient Deer Skull Headdress in Germany Hints at Early Cultural Connections