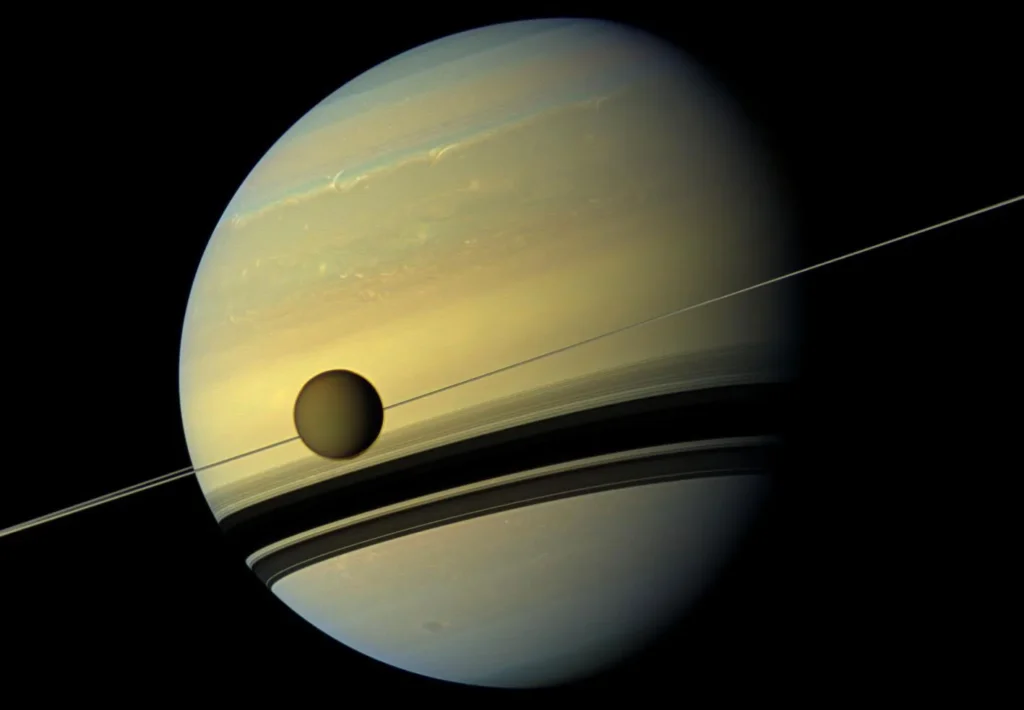

Scientists say Saturn’s Moon Titan is forcing a major rethink in planetary science after a new analysis of NASA spacecraft data challenged long-standing assumptions about its interior. Researchers reviewing measurements collected during the Cassini mission concluded Titan may not contain a vast underground ocean, as once believed. Instead, the moon likely has a partially frozen interior made of layered slushy ice, a finding that could reshape where scientists search for life beyond Earth.

Table of Contents

New NASA Data Is Changing What Scientists Think About Saturn’s Moon Titan

| Key Fact | Detail / Statistic |

|---|---|

| Mission | Cassini spacecraft studied Titan from 2004–2017 |

| New Discovery | Interior likely slushy ice layers, not a global ocean |

| Scientific Importance | Only moon with stable surface liquids |

The reinterpretation of Cassini data does not diminish Titan’s scientific importance. Instead, researchers say it expands the questions scientists can ask. As Lorenz noted, Titan continues to challenge expectations, and direct exploration in the coming decades may reveal whether its chemistry is merely complex — or a pathway toward life itself.

Saturn’s Moon Titan: Why It Has Long Fascinated Scientists

Titan, larger than the planet Mercury, orbits Saturn about 900 million miles (1.4 billion kilometers) from Earth. Among more than 200 known moons in the Solar System, it is widely considered the most Earth-like — not in temperature or habitability, but in environmental processes.

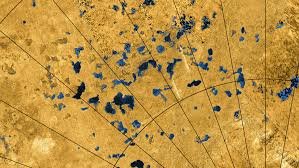

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) says Titan is the only known world besides Earth with stable liquids on its surface. Yet those liquids are not water. Instead, Titan’s rivers, lakes, and seas contain methane and ethane hydrocarbons.

The moon also has weather. Clouds form, storms develop, and rain falls. Channels carved into its landscape resemble river valleys on Earth.

Dr. Ralph Lorenz, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory and a scientist on NASA’s upcoming Dragonfly mission, said Titan offers an unusual natural laboratory.

“Titan combines weather, geology, and organic chemistry in a single world. Nowhere else we know does all of that occur together,” he said in a NASA briefing.

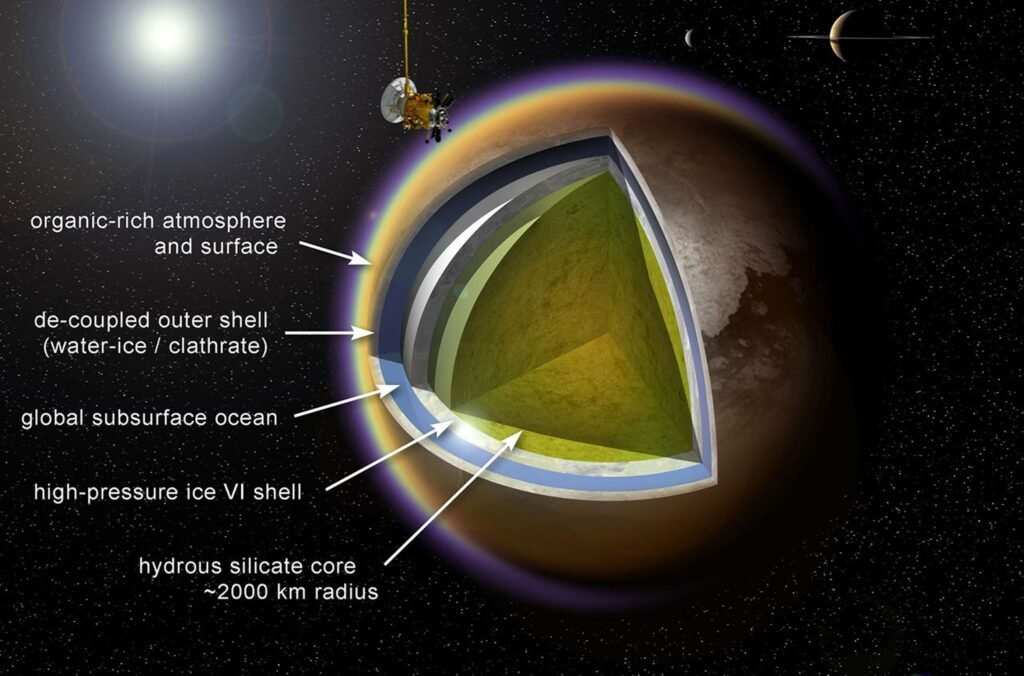

For years, researchers believed a deep global ocean of liquid water lay beneath Titan’s icy crust. The theory came from tidal measurements showing the moon’s outer shell flexed under Saturn’s gravity — a behavior expected if a liquid layer existed below.

New Data Reinterprets Cassini Measurements

Gravity Clues Inside the Moon

Scientists reanalyzed gravity readings collected during dozens of Cassini flybys between 2004 and 2017. The spacecraft tracked minute changes in its radio signal while passing Titan, allowing researchers to measure how the moon’s mass was distributed internally.

Planetary scientists use this method because internal layers — rock, ice, or liquid — affect a moon’s motion differently.

The updated analysis shows Titan does not deform as much as a large liquid ocean would predict. Instead, the best explanation is a thick ice shell over a mixture of partially melted ice and denser material — essentially a slushy interior.

Dr. Rosemary Pike, a planetary geophysicist who studies icy moons, explained the impact:

“A slushy interior would move more slowly under tidal forces. That matches the measurements better than a deep ocean model.”

Researchers say the structure could resemble frozen ice sheets on Earth’s polar regions, but hundreds of miles thick and under extreme pressure.

A Change in Planetary Classification

The finding shifts Titan’s scientific classification. It was long grouped with “ocean worlds,” a category that includes Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus. These worlds are thought to have global liquid oceans beneath ice shells.

Titan may still contain water, but not a single global sea. Instead, scientists now suspect localized pockets of liquid trapped inside layered ice.

That distinction matters because life depends not just on water, but on energy and chemistry interacting together.

Implications for the Search for Life

Not Worse — Possibly More Complex

The revised model does not eliminate the possibility of life. Some scientists say it may even improve it.

Slushy ice layers can trap heat produced by radioactive elements in Titan’s rocky core. That heat may create temporary liquid water chambers where organic molecules can react.

Titan’s atmosphere already produces complex carbon-based molecules when sunlight breaks apart methane gas. These molecules settle onto the surface over millions of years.

Laboratory simulations funded by NASA have shown certain compounds in Titan-like conditions can form membrane-like structures similar to primitive cell walls.

That does not confirm biology. But it shows chemistry capable of organizing itself into structures that resemble early biological systems.

Astrobiologist Dr. Sarah Hörst of Johns Hopkins University has previously explained Titan’s significance:

“Titan is not just a place to look for life as we know it. It may show us how life begins under completely different conditions.”

The Dragonfly Mission: A Flying Laboratory

NASA plans to test these ideas directly through its Dragonfly mission. The spacecraft, scheduled for launch in the late 2020s, will carry a nuclear-powered rotorcraft lander to Titan.

Unlike previous missions that landed in one location, Dragonfly will fly from site to site, traveling dozens of miles between sampling points.

It will:

- analyze surface materials,

- measure atmospheric chemistry,

- and search for prebiotic molecules.

Titan’s dense atmosphere and low gravity make flight practical. Engineers say a rotorcraft is more efficient there than a wheeled rover would be on Mars.

NASA’s Planetary Science Division describes Dragonfly as a mobile laboratory designed to test whether Titan’s chemistry can support biological processes.

Historical Context: From Telescope Observations to Spacecraft Exploration

Astronomers first observed Titan in 1655 when Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens discovered the moon using a telescope. For centuries, Titan appeared only as a blurry orange dot.

Its atmosphere hid the surface completely. Even large telescopes could not see through the haze.

The mystery began to clear in 2005 when the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe descended through the atmosphere and landed on Titan. Images revealed rounded ice pebbles and channels resembling dried riverbeds.

Later, Cassini’s radar instruments mapped seas and coastlines beneath the thick clouds.

Those discoveries established Titan as one of the most complex environments in the Solar System.

Why Titan Matters in Planetary Science

Scientists want to know how life begins. Earth offers only one example, making it difficult to determine whether life is rare or common.

Titan provides a second chemical environment where life-like processes might occur.

Mars shows evidence of ancient water. Europa and Enceladus contain subsurface oceans. But Saturn’s Moon Titan has both surface chemistry and possible internal water — a combination scientists consider especially valuable.

Many researchers believe early Earth once had a methane-rich atmosphere. Titan could resemble that ancient stage of planetary evolution.

By studying it, scientists may learn how simple molecules form complex systems capable of self-organization.

Broader Scientific Impact

The new understanding also affects how scientists interpret other icy worlds. If Titan — the Solar System’s most studied moon after Earth’s Moon — can be misinterpreted for decades, researchers say other worlds may require reevaluation as well.

Planetary scientist Dr. Jonathan Lunine of Cornell University has noted in past NASA research briefings:

“We are learning that planetary bodies are more complicated than our models predicted. Titan is teaching us humility about how planets work.”

FAQs About New NASA Data Is Changing What Scientists Think About Saturn’s Moon Titan

Is Saturn’s Moon Titan habitable for humans?

No. Surface temperatures average about −290°F (−179°C). The atmosphere lacks oxygen and contains hydrocarbons.

Why is methane important there?

Methane plays the same role water plays on Earth. It forms clouds, rain, rivers, and lakes.

When will Dragonfly arrive?

If launched as planned, the spacecraft would reach Titan in the mid-2030s after a multi-year journey through the outer Solar System.

Could Titan have life today?

Scientists do not know. The mission aims to determine whether prebiotic chemistry — the step before life — is occurring.