Ancient Bones Show Rituals Performed: Long before the pyramids, the Roman Empire, or even written history, people were already fighting — and they weren’t doing it quietly. Recent archaeological discoveries in France have revealed something downright chilling yet fascinating: ancient bones show rituals performed after Europe’s earliest battles. This evidence, buried for over 6,000 years, suggests that violence wasn’t just about survival. It was about power, pride, and community — and those who won the fight made sure everybody knew it. These rituals weren’t random acts of brutality. They were structured, meaningful, and possibly even spiritual. And they change everything we thought we knew about how organized warfare — and society — began.

Table of Contents

Ancient Bones Show Rituals Performed

The discovery that ancient bones show rituals performed after Europe’s earliest battles changes our view of human history. It tells us that early communities didn’t just survive war — they interpreted it, ritualized it, and used it to build identity. These were not acts of random savagery. They were expressions of meaning, memory, and control. And through science, we now have the tools to understand what those silent bones have been trying to tell us for thousands of years. As we continue to uncover humanity’s earliest conflicts, one thing becomes clear: history isn’t written just in words — it’s carved in bone.

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| Main Discovery | Ritualized violence after early battles in Europe |

| Time Period | ~4300–4150 BCE (Late Neolithic Era) |

| Locations | Alsace region, France (Achenheim & Bergheim sites) |

| Key Evidence | Blunt-force trauma, severed limbs, non-local isotopic markers |

| Scientific Methods | Multi-isotope analysis, osteology, site comparison |

| Why It Matters | Suggests early warfare was symbolic and ceremonial |

| Cultural Significance | Highlights group identity, propaganda, and early ritual |

| Official Reference | Oxford University Research |

The Story in the Soil: What the Bones Tell Us

Archaeologists excavating mass graves in northeastern France — particularly at Achenheim and Bergheim — uncovered human remains dated to 4300–4150 BCE. But these weren’t just regular burials.

- Multiple skeletons showed clear signs of blunt-force trauma, especially to the skull and ribs.

- Dozens of left upper arms had been cleanly severed and placed together in ditches.

- Advanced testing revealed that many individuals weren’t from the region — they were outsiders, likely enemies captured or killed in conflict.

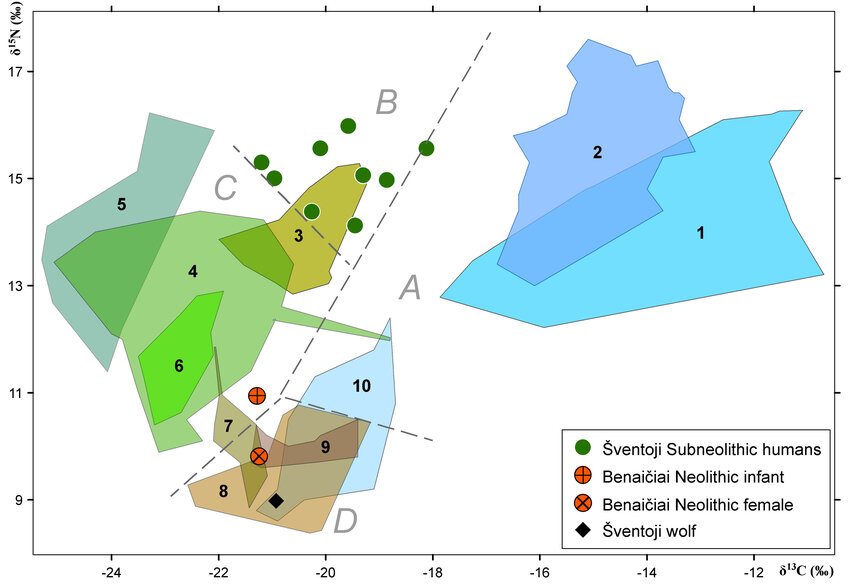

That last point is key. Using multi-isotope analysis, scientists examined the chemical composition of the teeth and bones to determine geographic origin. Many of the dead had traveled long distances before dying in these battles, suggesting that what we’re seeing isn’t just local violence — it’s inter-group warfare, likely over territory, resources, or dominance.

Purpose Behind the Ancient Bones Show Rituals Performed: Why These Rituals Were Performed

These findings point to something deeper than mere survival instinct. Let’s break down why ancient humans would go to such lengths after battle:

1. Demonstrating Power Publicly

Much like how modern societies host parades or medal ceremonies, ancient communities showcased their victories. Severed arms may have served as physical trophies — proof that their enemies were defeated.

But this wasn’t just about showing off. It was a message to the tribe and to outsiders: “This is what happens when you cross us.”

2. Cementing Group Identity

Victory rituals weren’t only about the fallen — they were about the living. These acts likely served to unite survivors, helping them process trauma and reaffirm their shared identity. Picture the emotional surge of a tribal chant or a modern national anthem — now add the visceral presence of a severed limb or a battle-scarred skull.

3. Psychological Warfare

Some remains showed signs of execution after capture, including repeated trauma inconsistent with immediate death. That tells us captives were likely tortured or displayed, not simply killed in combat. These actions weren’t about efficiency — they were about sending a warning.

The Bigger Picture: How Ancient Bones Show Rituals Performed Changes Our Understanding of History

For decades, scholars believed large-scale, organized warfare didn’t emerge in Europe until the Bronze Age, roughly 3000 BCE. But this discovery pushes that timeline back by nearly a millennium, revealing that even early farming communities had complex social structures and ritualistic violence.

This also reshapes how we view Neolithic people. They weren’t simple farmers living in peace. They had politics. Strategy. Ceremony. They recorded victory not in ink, but in bone.

The Science Behind the Ancient Bones Show Rituals Performed Discovery

You might be wondering — how do researchers know all this? Here’s the breakdown:

Multi-Isotope Analysis

- Isotopes in tooth enamel and bones show what kind of food and water a person consumed during life.

- Different regions leave distinct isotopic “signatures.”

- The tests confirmed that many victims were non-locals, indicating inter-regional conflict.

Osteological Analysis

- Repeated trauma to the same bone indicates ritualized killing, not just battlefield death.

- Some skeletons had healed injuries, meaning they were likely veterans or warriors, not civilians.

- Presence of children and women among the remains suggests community-wide targeting, not selective military clashes.

Pattern Matching

- Sites in Germany (Talheim) and Austria (Asparn/Schletz) show similar burial styles, mass killings, and trophy practices.

- This implies cross-cultural practices or shared belief systems about war and death during the Neolithic period.

Connections to Modern Society

While today’s rituals don’t usually involve severed limbs (thankfully), we still carry many echoes of these ancient practices.

War Memorials and Ceremonies

Every time a soldier is honored, a flag is folded, or a memorial is erected, we’re engaging in rituals that assign meaning to violence and loss — much like these Neolithic ceremonies.

Sports and Symbolic Rivalry

From high school football rivalries to Olympic medal counts, we use symbolic displays of competition and victory to strengthen group identity. We just swap bones for trophies and chants.

Educational Applications: Bringing This into the Classroom

This topic isn’t just for academics — it’s a gold mine for educators.

For Teachers

- Use interactive maps to track the movements of these ancient communities.

- Host mock archaeological digs using replica bones to teach students about forensic techniques.

For Museums and Public Programs

- Develop immersive exhibits showing how isotope analysis works.

- Create storytelling spaces where visitors can “hear” what life was like after these battles.

For College Curricula

- Introduce this case in anthropology, sociology, and history courses to show the evolution of social rituals and power structures.

Professional and Research Implications

These findings open up major new paths for research and professional exploration:

- Military historians can now trace ceremonial aspects of warfare to earlier periods than previously thought.

- Cultural anthropologists can investigate how early rituals influence modern ones.

- Public archaeologists can better engage communities by relating ancient practices to today’s social structures.

Expanding the Conversation: What It Means for Us Today

So why should we care about ancient bones and rituals? Because history is a mirror — and this mirror shows us that:

- Humans have always used symbolic acts to manage conflict.

- We often ritualize trauma to make it bearable — whether through funerals, memorials, or monuments.

- Understanding early violence helps us understand modern group behavior, from nationalism to tribalism.

The core takeaway? Violence isn’t just chaos. It’s often a performance, a narrative, a tool for identity. And we’ve been using that tool for a very long time.

Ancient Creatures From 325 Million Years Ago Found in Mammoth Cave

Could Earth Bear Traces of Ancient Engineering? A Controversial Idea Emerges

Archaeologists Discover a Rare Lead Pipeline in Petra’s Ancient Aqueduct