An international research team says a 2000-Year-Old Roman Board Game has been decoded after computer simulations reconstructed how a mysterious carved stone from a Roman settlement was played. The February 2026 study concludes Romans engaged in structured strategic thinking, revealing leisure culture in the ancient empire was more intellectually complex than historians previously believed.

Table of Contents

2000-Year-Old Roman Board Game

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Location | Roman town Coriovallum (modern Heerlen, Netherlands) |

| Method | AI simulations compared with wear patterns |

| Game Type | Positional blocking strategy game |

| Estimated Age | ~2,000 years |

The research team says the method may soon reveal forgotten pastimes from other ancient cultures. By combining archaeology and artificial intelligence, scientists are no longer only studying ancient objects — they are recreating how people thought and interacted nearly two thousand years ago.

How Researchers Solved the Mystery

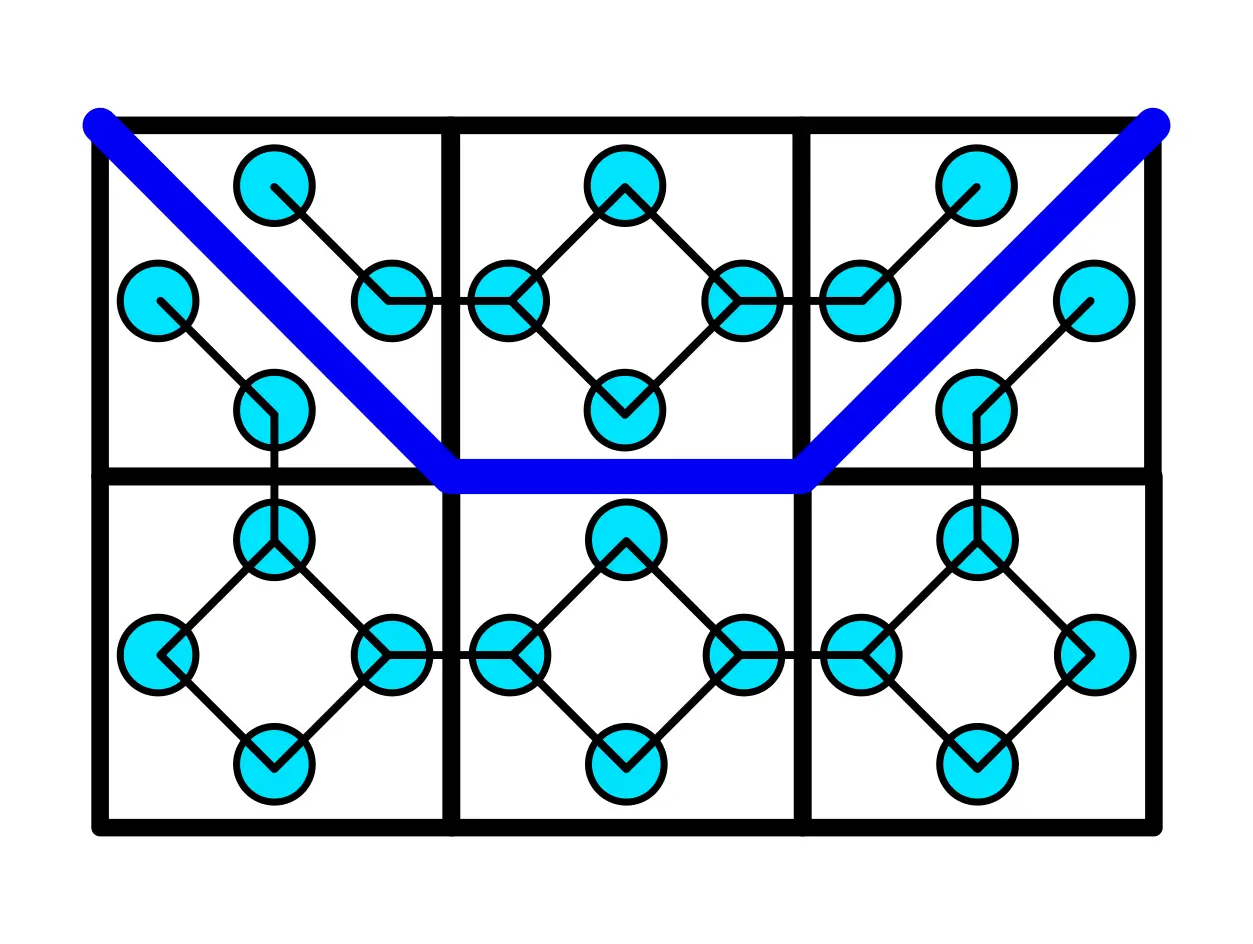

Archaeologists discovered the small limestone slab in Heerlen several years ago, but its purpose remained unclear. The carving showed intersecting lines and circular nodes. It resembled a game board, yet no surviving Roman writings described a matching design.

To investigate, scientists turned to computational archaeology — a growing discipline combining digital modeling with historical analysis.

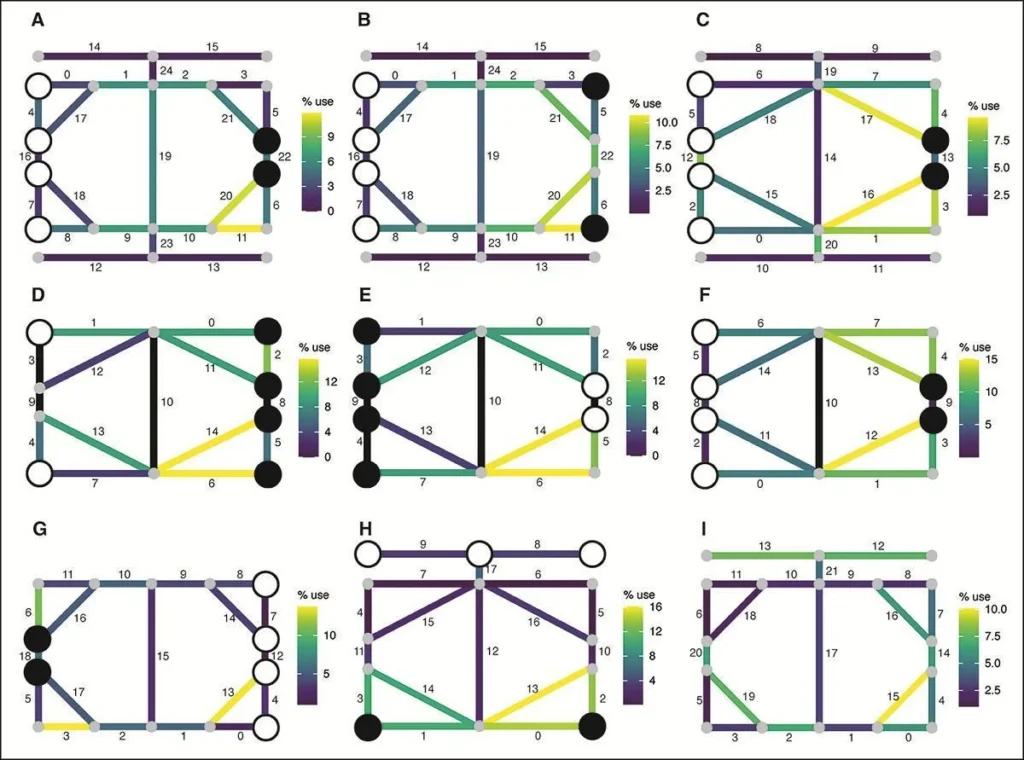

The team digitized the board and used a historical game-reconstruction platform called Ludii. Artificial players ran thousands of matches under dozens of possible rule systems. Researchers then compared simulated movement paths to microscopic wear marks on the actual stone.

“The wear patterns act like fingerprints of behavior,” one of the study’s authors explained in the research publication. “If simulated play produces the same patterns, it strongly suggests people once used those rules.”

Unlike many Roman artifacts, the board lacked inscriptions. Traditional archaeology therefore had limited evidence to interpret it. Instead of relying on texts, researchers examined use-based physical traces.

Microscopic abrasion showed repeated motion between specific nodes on the board. When the AI adopted certain rule systems, its movements created identical pathways. Those simulations became the most likely reconstruction of the game’s rules.

The Rules No One Expected

A blocking strategy, not a battle game

The simulation revealed a surprising conclusion. The reconstructed game did not resemble chess, checkers, or Roman military capture games such as Latrunculi. Instead, it worked as a positional blocking contest.

Two players likely competed using unequal numbers of pieces — one controlling four pieces and the other two.

Rather than capturing opponent pieces, the goal was immobilization. The winner was the player who trapped the opponent so no legal moves remained.

This type of gameplay is known in modern game theory as a “zugzwang-like” condition, where the opponent loses because every available move worsens their position.

Historians had long believed this style of positional strategy game became common in Europe during the medieval period. The new findings suggest it existed centuries earlier.

“This pushes back our understanding of abstract strategic thinking in Roman recreation,” the researchers wrote.

What a typical match likely looked like

Based on simulations, researchers believe a match followed several phases:

- Initial placement of pieces on specific nodes

- Alternating movement along engraved lines

- Gradual territorial restriction

- Final entrapment of one player’s pieces

Games likely lasted only minutes, suggesting it functioned as casual entertainment — similar to modern tabletop strategy games played in cafés or waiting areas.

What It Says About Roman Society

Beyond gambling and dice

Roman leisure is often associated with betting games and dice, common in taverns and military camps. However, archaeologists say the board indicates structured intellectual play.

The location matters. Coriovallum was a frontier settlement along important trade routes connecting military roads in the Roman Empire. Soldiers, merchants, and travelers interacted daily.

Experts say games often traveled with armies. Roman soldiers stationed far from home used games to relieve boredom and maintain social bonds.

Historians of ancient culture say board games served several purposes:

- training logical thinking

- teaching patience and planning

- bridging language barriers among diverse populations

- maintaining morale in remote garrisons

The research team named the reconstructed game Ludus Coriovalli, after the ancient town.

Comparison With Other Ancient Games

Understanding the 2000-Year-Old Roman Board Game becomes clearer when compared to known ancient games.

Latrunculi

Often called the “Roman chess,” Latrunculi involved capturing enemy pieces and mimicked military tactics.

Nine Men’s Morris

This Roman-era game, still played today, focused on forming lines of pieces to remove opponent counters.

Egyptian Senet

Played 3,500 years ago, Senet combined strategy and luck with religious symbolism.

The newly reconstructed game differs from all three because it centers entirely on mobility restriction. That makes it closer to modern abstract strategy games than to war simulations.

Historians say this suggests Roman intellectual culture included recreational logic puzzles, not just symbolic or military games.

Why Artificial Intelligence Matters to Archaeology

The study illustrates a broader shift in historical research methods. Instead of interpreting objects only visually, scientists increasingly analyze how objects were used.

Wear marks — scratches, polishing, and grooves — preserve behavioral evidence.

By simulating thousands of matches, AI identified the rule set most likely to produce the observed abrasion. Researchers say this technique could help decode many unexplained carvings found across Europe and the Middle East.

Potential future applications include:

- scratched tavern tables

- temple carvings

- engraved stones in military forts

- graffiti boards found in Pompeii

Computational archaeology has also been used to reconstruct broken inscriptions, predict missing architecture, and model ancient city populations.

Researchers say gaming artifacts are especially suitable because rules generate measurable movement patterns.

Scholarly Reaction

Historians say the discovery could change assumptions about early European game development.

Many believed complex abstract strategy evolved alongside medieval chess traditions introduced around the early second millennium. The reconstructed Roman game suggests structured logic games existed in everyday Roman life much earlier.

Archaeologists studying social history emphasize that games reveal behavior often missing from official records.

Monuments describe rulers. Games describe people.

“This is social history preserved in stone,” a historian noted in commentary discussing the research. “You are seeing how ordinary individuals thought, competed, and relaxed.”

Researchers also say the find helps historians understand Roman education. Strategic thinking games may have helped children and young soldiers learn planning and foresight.

Everyday Life in the Roman Empire

The 2000-Year-Old Roman Board Game also sheds light on daily routines. Roman settlements included baths, taverns, markets, and communal spaces where people gathered.

Boards carved into stone benches and steps have been found across former Roman territories, including Britain, Syria, Egypt, and North Africa. Many were previously dismissed as decorative scratches.

Scholars now suspect some represent unknown games.

Roman writers described leisure as important for mental balance. Philosophers including Seneca encouraged structured recreation to maintain discipline and clarity of thought.

This discovery supports those writings with physical evidence.

What Happens Next

Researchers plan to publish playable versions so the public can test the reconstructed rules.

Museums may introduce interactive exhibits allowing visitors to compete against AI versions of ancient players. The team also plans to apply the same methodology to other artifacts already stored in museum collections.

Archaeologists say many stone carvings discovered in earlier excavations were never studied closely because researchers lacked tools to analyze wear behavior.

With AI modeling now available, some museums are re-examining artifacts excavated decades ago.

If confirmed, scholars say dozens of unknown ancient games could soon be reconstructed.

FAQ

What is Ludus Coriovalli?

It is the reconstructed name given by researchers to the Roman board game discovered in the Netherlands.

Why is the discovery important?

It shows Romans played strategic positional games centuries earlier than historians believed.

How did scientists know the rules?

They compared computer-simulated play patterns to microscopic wear marks on the stone board.

Was it a gambling game?

Evidence suggests it was a strategy game rather than a dice-based betting activity.

Can people play it today?

Researchers plan public digital versions based on the reconstructed rules.