The debate over renewable energy often turns into a debate about land. Farmers worry about losing productive fields to solar power projects, while energy planners worry about finding enough space to expand clean electricity.

A growing body of research is now challenging the idea that agriculture and solar energy must compete. Instead, scientists are exploring ways both can coexist on the same land — and the results are far more complex than many expected. Recent field trials and economic studies show that installing solar panels on farmland does not automatically reduce agricultural productivity.

In fact, in some situations it can improve it. Researchers have observed changes in plant growth, soil moisture, and farm income when crops are grown beneath elevated solar structures. These changes vary by crop type, climate, and system design, but one conclusion is clear: combining farming and solar energy reshapes both crop yields and farm economics.

Table of Contents

Agrivoltaics

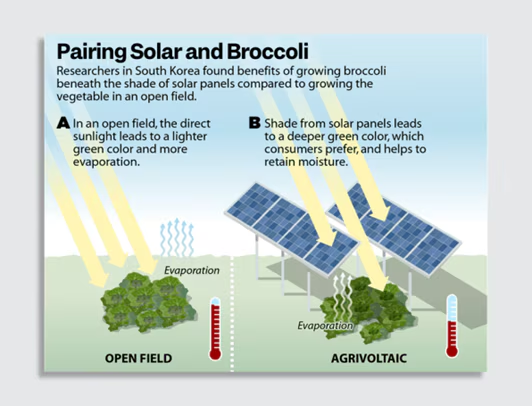

Agrivoltaics is the practice of growing crops under or between raised solar panels so that land produces both electricity and food at the same time. Instead of replacing farmland, the system modifies how sunlight, temperature, and water interact with crops. Studies show the partial shade created by panels can reduce heat stress, limit evaporation, and protect plants from extreme weather. This means solar infrastructure can act not just as an energy generator, but as part of the farm environment itself.

Solar Panel Farming

| Aspect | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Land Use | Produces electricity and crops on the same field |

| Crop Yield | Increases for shade-tolerant crops, decreases for sun-loving crops |

| Soil Effects | Cooler soil and higher moisture retention |

| Water Use | Reduced evaporation and improved drought resilience |

| Farm Income | Additional income from electricity or land lease |

| Risk | Lower financial risk due to diversified earnings |

| Best Crops | Vegetables, herbs, berries, specialty crops |

| Challenging Crops | Wheat, maize, and other full-sun cereals |

| Design Factors | Panel height and spacing significantly affect outcomes |

Crop Yield: It Can Increase — But Not for Every Crop

One of the most important discoveries from recent research is that solar panels do not have a single predictable effect on crops. Some plants benefit from the filtered sunlight created by the panels. Others struggle without full exposure.

Shade-tolerant plants often perform well in these conditions. Vegetables, herbs, and specialty crops have shown improved growth in several trials. The panels reduce midday heat and protect leaves from intense radiation. Because temperatures stay lower, plants experience less stress, especially during hot seasons. This can lead to healthier foliage and longer growing periods.

However, crops that depend heavily on direct sunlight respond differently. Cereal grains such as wheat, rice, and maize require strong light for photosynthesis. Under shaded conditions, their energy production drops, which can reduce harvest volumes. Some studies observed noticeable yield declines in these crops when shading was excessive.

The key takeaway is not that solar farming harms agriculture, but that crop selection matters. The same system that improves vegetable production may reduce grain output.

Why Panels Can Increase Yields

Researchers have identified several reasons crops may grow better under solar panels.

First, the panels lower temperature extremes. During hot afternoons, shaded soil remains cooler. High heat usually causes plants to close their stomata, slowing growth. By reducing heat stress, the plants continue normal development.

Second, evaporation decreases. Soil under panels retains moisture longer because sunlight is partially blocked. This reduces irrigation needs and helps crops survive dry spells.

Third, the structures act as wind barriers. Strong winds can damage plants and increase water loss. Panels moderate airflow, creating a more stable microclimate.

In hot climates especially, this combination acts almost like a protective cover for crops. Instead of competing with farming, the panels can function as agricultural infrastructure.

Why Panels Can Decrease Yields

Despite the benefits, not all results are positive. The primary issue is reduced sunlight intensity. Photosynthesis depends on light energy. When shading becomes too strong or too constant, plant growth slows.

Tall cereal crops and sun-loving plants require uninterrupted light exposure for much of the day. If panels are too low or too densely spaced, they block a large portion of sunlight. This directly reduces biomass production and grain formation.

In poorly designed systems, farmers may experience lower harvests. Therefore, installation design — not just the presence of panels — determines success.

Soil and Water Effects (A Newer Discovery)

More recent research has moved beyond plant growth and started examining soil conditions. Scientists found that solar installations alter the physical environment of farmland.

Under the panels, soil temperature is lower and moisture levels are higher. These conditions support microbial activity in the soil, which plays a crucial role in nutrient cycling. Healthier soil microbes improve plant nutrient absorption and long-term fertility.

Another significant effect is drought resilience. Because evaporation drops, crops can survive longer periods without rain. In dry regions, this benefit may be as important as yield changes.

In short, solar panels do not only affect crops above the ground — they also influence the ecosystem below it.

Farm Economics: The Surprising Part (Costs & Income)

Perhaps the most dramatic finding of agrivoltaic research is economic rather than agricultural. Solar panels provide farmers with a second revenue stream.

Farmers can lease land for solar installations or sell generated electricity. This creates predictable annual income regardless of crop success. Unlike harvests, electricity production does not depend on rainfall, pests, or market prices.

Because of this, solar installations reduce financial risk. A bad growing season no longer means zero income. The farm effectively gains a second “crop,” one that does not fail due to drought or disease.

The combined revenue from crops and energy often exceeds what agriculture alone could provide. For many farmers, the financial stability may be more important than changes in yield.

Why Results Vary So Much

Research shows outcomes depend heavily on system design.

Panel height is critical. Higher panels allow more sunlight to reach crops and enable farm equipment to pass underneath. Spacing between panel rows also matters. Wider gaps reduce shading and improve airflow.

Orientation and tilt influence how shadows move during the day. Moving shadows can actually help crops by preventing prolonged darkness in one area.

Climate also plays a major role. Hot regions benefit most because shading reduces heat stress. Cooler regions may see smaller advantages.

Therefore, agrivoltaics is not a single standard technology. Each installation must be adapted to crop type and local weather conditions.

What This Means for Farming

The idea that solar power automatically removes farmland is no longer accurate. The research suggests a different future — farmland that produces both energy and food simultaneously.

Some crops will need to be chosen carefully. Others may thrive. Soil health can improve, water use may decline, and farmers gain a stable income source. The challenge is proper planning and design.

The overall conclusion emerging from recent studies is straightforward: solar panels do not replace agriculture. When implemented thoughtfully, they transform how farming works.

Instead of a conflict between food production and renewable energy, agrivoltaics offers a shared solution — land that feeds people while also powering their homes.