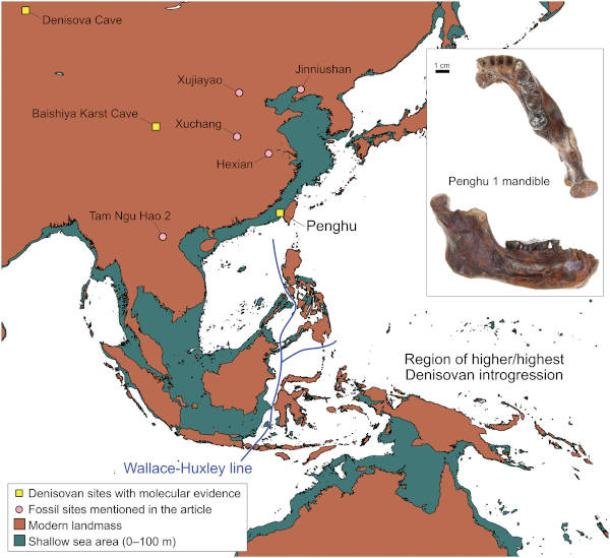

Denisovan Fossil Found Under the Ocean: Denisovan Fossil Found Under the Ocean May Rewrite Early Human Migration History is not just a dramatic science headline—it reflects a real, peer-reviewed breakthrough that is reshaping how researchers understand ancient human dispersal across Asia. When scientists confirmed that a fossilized jawbone recovered from the seabed near Taiwan belonged to a Denisovan, it expanded the known geographic range of this mysterious archaic human group and challenged long-standing migration models.

As someone who has spent years studying paleoanthropology research and watching how new data reshapes old theories, I can say this discovery carries weight. It isn’t about hype. It’s about careful analysis, molecular testing, and global collaboration. And while the science behind it involves complex protein sequencing and stratigraphic modeling, the big idea is something anyone can understand: our ancient relatives traveled farther and adapted better than we once thought. The fossil—known as Penghu 1—was originally recovered by fishermen dredging the Penghu Channel between mainland China and Taiwan. For years, researchers debated whether the jawbone belonged to a Denisovan, a Neanderthal, or another archaic human lineage. Only recently did advanced protein analysis confirm its identity. That confirmation has implications stretching from genetics to underwater archaeology.

Table of Contents

Denisovan Fossil Found Under the Ocean

The Denisovan Fossil Found Under the Ocean May Rewrite Early Human Migration History represents a turning point in paleoanthropology. By confirming Denisovan presence in subtropical East Asia, researchers have expanded the map of ancient human habitation and reinforced the complexity of early human migration. This discovery reminds us that science is dynamic. New tools like protein sequencing can breathe life into old fossils. Submerged landscapes hold untapped evidence. And our human story—woven through climate change, migration, and adaptation—is far richer than once imagined. As researchers continue exploring ancient coastlines and applying advanced molecular techniques, we can expect more surprises. Each new find adds another piece to the puzzle of who we are and where we came from.

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| Discovery Location | Penghu Channel, near Taiwan |

| Fossil Identified As | Denisovan male mandible (“Penghu 1”) |

| Estimated Age | Between ~10,000 and 190,000 years old |

| Identification Method | Paleoproteomics (ancient protein analysis) |

| Geographic Significance | Extends Denisovan range into subtropical East Asia |

| Sea Level Context | Ice Age sea levels ~300 feet lower than today (USGS) |

| Genetic Legacy | Up to 5% Denisovan DNA in some modern populations |

| Official Scientific Source | Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology – https://www.eva.mpg.de |

Understanding Denisovans in Plain Terms

To understand why this matters, let’s step back.

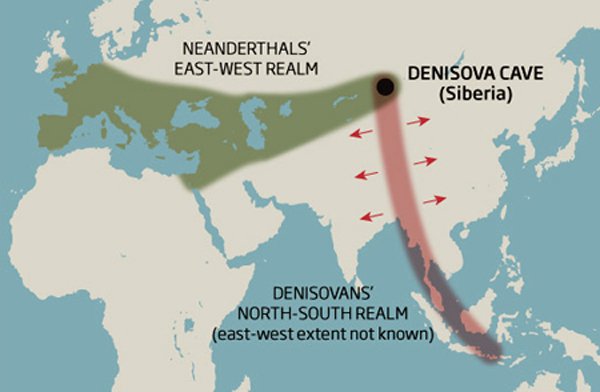

Denisovans are an extinct group of archaic humans first identified in 2010 from a finger bone discovered in Denisova Cave in Siberia. That groundbreaking genetic study was conducted by the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and published in Nature. Unlike Neanderthals, Denisovans were initially known almost entirely from DNA rather than complete skeletons.

Since that discovery, genetic evidence has shown that Denisovans interbred with early Homo sapiens. According to research published in Nature, populations in Papua New Guinea and parts of Oceania carry as much as 3–5% Denisovan DNA. Some East and Southeast Asian populations also carry smaller but significant percentages.

This isn’t just abstract science. It means Denisovans contributed directly to the genetic makeup of millions of people alive today. Some inherited traits—such as adaptations to high-altitude environments—are linked to Denisovan ancestry. Research from Harvard Medical School has shown that a gene variant helping Tibetan populations thrive at high elevations likely came from Denisovans.

So when a Denisovan fossil appears far from Siberia, it reinforces the idea that these ancient humans were widespread and adaptable.

The Discovery of Penghu 1

The Penghu fossil was dredged from the ocean floor in the Penghu Channel, an area submerged today but once dry land during the Ice Age. During glacial periods, global sea levels were dramatically lower because vast amounts of water were locked in ice sheets.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, sea levels during the Last Glacial Maximum were about 300 feet (roughly 90 meters) lower than today. That means the region where Penghu 1 was found was once part of an exposed continental shelf connecting mainland Asia to Taiwan.

For years, researchers debated the fossil’s classification. The mandible showed:

- Thick, robust bone structure

- Large molars

- Absence of a pronounced chin

Those traits suggested an archaic human species. However, morphology alone wasn’t enough for definitive classification.

DNA extraction failed due to tropical climate degradation. Warm, humid conditions accelerate DNA breakdown. That’s where paleoproteomics changed the game.

Denisovan Fossil Found Under the Ocean: How Protein Analysis Solved the Puzzle

When DNA cannot be recovered, scientists turn to proteins. Proteins are made of amino acids and can survive longer than DNA in certain fossil conditions.

In a study published in Science, researchers extracted ancient proteins from the Penghu mandible and compared their amino acid sequences to known Denisovan and Neanderthal samples. The protein signatures matched Denisovan profiles.

This was a major milestone because it demonstrated that Denisovans lived in subtropical East Asia, not just cold northern climates. It also confirmed that protein analysis is a powerful tool in paleoanthropology, especially in regions where DNA preservation is poor.

The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History has highlighted paleoproteomics as one of the most promising methods for studying ancient human remains in tropical environments.

Denisovan Fossil Found Under the Ocean: Why Geography Changes the Story

For decades, textbooks suggested Denisovans primarily occupied northern Asia. Most fossil evidence came from Siberia and the Tibetan Plateau.

The Penghu discovery shifts that understanding.

If Denisovans were living near present-day Taiwan, they likely inhabited:

- Coastal plains

- River systems

- Forested subtropical environments

- Regions that are now underwater

This means migration corridors were broader than previously assumed. It also suggests that Denisovans may have encountered early Homo sapiens across multiple points in Asia—not just isolated mountain regions.

Genetic modeling supports this idea. Studies indicate at least two distinct Denisovan admixture events in human history. That implies complex interactions over time and space.

Climate Change and Submerged Landscapes

One of the most fascinating aspects of this discovery is its underwater location.

During the Ice Age, large portions of today’s ocean floor were habitable land. When glaciers melted around 11,700 years ago, sea levels rose rapidly, submerging coastlines and migration routes.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration explains that post-glacial sea level rise dramatically reshaped global geography.

This means significant archaeological evidence may still lie beneath the ocean.

Underwater archaeology is becoming increasingly important. Institutions such as Texas A&M University’s Nautical Archaeology Program are training specialists to explore submerged sites.

For professionals in anthropology, geology, and marine science, this represents a frontier field. The Penghu fossil may be only the beginning.

Broader Implications for Human Evolution

Let’s talk about what this means for the big picture.

Human evolution is not a straight line. It’s more like a braided river with streams splitting and rejoining.

Denisovans were one branch of that river. Neanderthals were another. Homo sapiens—our branch—interacted with both.

The Penghu discovery supports the idea that Asia was home to a diverse mosaic of human groups interacting over thousands of years. It challenges older models that portrayed archaic humans as isolated and geographically restricted.

It also highlights how science evolves. In 2010, Denisovans were barely known. Today, they are central to discussions about migration, adaptation, and genetic diversity.

Practical Lessons for Students and Researchers

If you’re a student interested in anthropology or genetics, here are practical takeaways:

- Interdisciplinary skills matter. Modern paleoanthropology combines molecular biology, geology, climate science, and archaeology.

- Technology drives discovery. Paleoproteomics allowed this breakthrough when DNA failed.

- Climate data informs archaeology. Understanding sea-level changes is essential for mapping ancient migration routes.

- Global collaboration is key. This research involved international teams sharing data and resources.

For professionals, the Penghu fossil underscores the importance of revisiting older finds with new technology. Sometimes answers are waiting in museum collections.

Economic and Academic Impact of Denisovan Fossil Found Under the Ocean

Beyond the scientific implications, discoveries like this influence research funding and academic priorities.

Agencies such as the National Science Foundation fund evolutionary research projects that explore human origins and climate impacts. As underwater archaeology gains attention, funding opportunities may expand.

Universities may also develop new programs focusing on marine geoarchaeology and biomolecular anthropology.

For museums and science communicators, discoveries like Penghu 1 offer opportunities to engage the public in understanding how science works—carefully, methodically, and transparently.

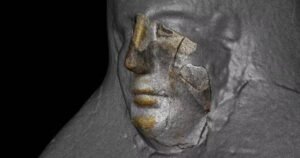

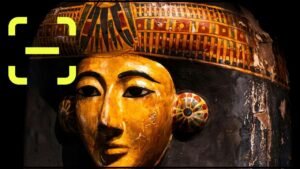

3D Technology Helps Reassemble Fragments of an Egyptian Mummy Mask

Fossil Team Finds Whale Remains Far from Any Coastline – Check Details

Study Suggests Two Early Human Species Migrated Out of Africa Together