Researchers have used Ancient Egyptian Mummy Mask reconstruction technology based on high-precision 3D scanning to reunite pieces of a funerary artifact that had been separated across museum collections for decades. The work, announced in February 2026 by an international team of archaeologists and conservation scientists, digitally reconstructed a broken mask without physically moving the fragile remains and restored clues about its original burial context.

Table of Contents

3D Scanning Technology

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Method | High-precision 3D metrological analysis comparing fracture geometry |

| Artifact | Painted cartonnage mummy mask fragments held in different museums |

| Impact | Reconnects artifacts to burial history and cultural identity |

Researchers say the project demonstrates how scientific imaging can reconnect global collections and recover human stories lost to time. As one conservation scholar noted, future museum cooperation may occur through shared digital archives, allowing ancient history to be reconstructed without moving a single artifact.

How Ancient Egyptian Mummy Mask Reconstruction Enabled a Scientific Match

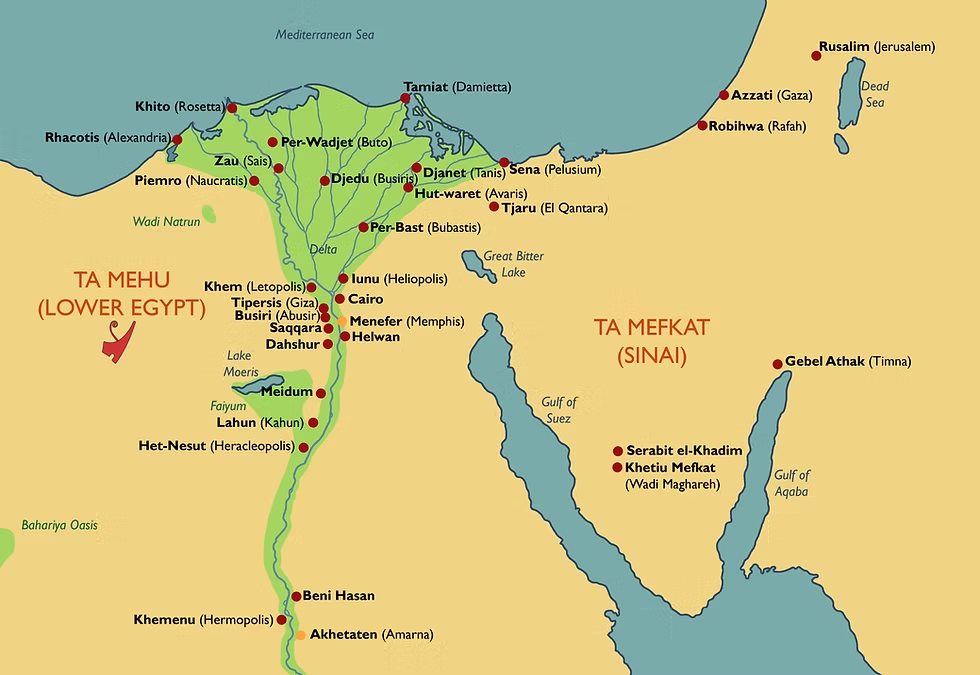

Archaeologists have long struggled with “orphaned artifacts” — items excavated in the 19th and early 20th centuries but separated during distribution to international museums. Poor documentation left many objects disconnected from their tombs.

The new research used ultra-precise 3D scanners to create digital models of each fragment. Scientists then compared curvature, thickness, and break-edge patterns. The pieces aligned with extremely small deviation, indicating they once formed a single funerary mask.

“This approach allows us to test connections scientifically rather than visually,” explained a conservation imaging specialist involved in the project. “The edges behave like fingerprints. If they match mathematically, the association is almost certain.”

Why Geometry Matters

Traditional identification relied on stylistic comparison — paint colors, iconography, or artistic style. However, artistic styles were often shared among workshops, making certainty difficult.

Digital modeling instead evaluates physical structure. The software overlays fragments and calculates whether fracture lines connect like a puzzle. When they match, the probability of a common origin is extremely high.

Rebuilding History Through Digital Archaeology

The mask is made of cartonnage, a material composed of layered linen or papyrus coated in plaster and painted. Such masks were placed over a deceased person’s face in ancient Egyptian burials to preserve identity in the afterlife.

Ancient Egyptians believed a preserved identity allowed the soul, or ba, to recognize the body. Masks therefore had religious importance beyond decoration.

Over decades, excavation sharing practices distributed fragments worldwide. Some pieces entered European and North American collections, while others remained in different institutions. Researchers digitally reunited them for the first time.

The reconstruction allows scholars to analyze:

- burial craftsmanship

- workshop production techniques

- social status of the deceased

- regional funerary customs

Experts describe the project as part of digital archaeology, a growing discipline using imaging, computing, and artificial intelligence to interpret ancient material culture.

Historical Context: Why the Mask Was Broken Apart

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, archaeological expeditions often operated under a system called partage. Excavated artifacts were divided between Egypt and sponsoring foreign institutions.

Record-keeping varied widely. Labels were handwritten, excavation maps were incomplete, and sometimes objects were separated after shipping. Over time, museum catalog numbers changed and connections were lost.

As a result, a single burial assemblage could end up scattered across continents.

Today, museums worldwide hold thousands of pieces whose original relationships remain unknown. The Ancient Egyptian Mummy Mask project demonstrates that technology can recover that lost information.

Museums and Cultural Heritage Implications

Conservation professionals say the discovery highlights a broader issue: museum collections may unknowingly contain parts of the same object.

Thousands of artifacts lack reliable excavation records. Reconnecting them restores historical context and improves scholarly accuracy.

Museum curators also see ethical implications. Reconstructed objects can help identify precise origins, strengthening provenance research and informing cultural heritage discussions.

Some institutions are now considering shared digital databases that allow automatic comparison of scanned artifacts globally.

The Technology Behind the Reconstruction

Structured-Light Scanning

The team used structured-light scanners that project patterned light onto surfaces. Cameras record distortions to calculate precise 3D coordinates.

The technique can measure surface variation smaller than one millimeter — roughly the thickness of a fingernail.

3D Metrological Analysis

After scanning, specialized software analyzes:

- surface topology

- curvature gradients

- fracture geometry

- material thickness

The analysis resembles forensic reconstruction used in engineering failure investigations and forensic anthropology.

Non-Destructive Research

Importantly, researchers never physically attached the fragments. The entire reconstruction occurred digitally, protecting fragile materials from stress.

What the Mask Reveals About the Person

Researchers believe the mask likely dates to Egypt’s Late Period or early Ptolemaic era (approximately 664–200 BCE), a time when funerary art became more standardized but still individualized.

Paint traces suggest:

- layered pigments

- gilded details

- stylized facial proportions

Scholars may also estimate the individual’s social standing. More elaborate masks often belonged to priests, administrators, or elite families.

Although the individual’s name remains unknown, inscriptions and artistic style may eventually identify the burial region.

Wider Scientific Applications

The same approach is already influencing multiple fields:

Medicine

CT scanning and 3D modeling are used to virtually unwrap mummies, revealing diseases such as arthritis, dental infections, and cardiovascular conditions.

Paleontology

Scientists reconstruct dinosaur skeletons from scattered bones using digital alignment methods similar to the mummy mask reconstruction.

Forensics

Crash investigators reconstruct accidents by digitally aligning fractured components, demonstrating the crossover between archaeology and engineering science.

Future of Collaborative Museums

Researchers envision international digital repositories where museums upload artifact scans.

Computers could automatically compare geometry worldwide, detecting matches within seconds. A fragment in London could connect to a piece in Cairo or New York without shipping artifacts.

Conservation scientists say this would transform museum research, allowing institutions to collaborate without risking fragile objects.

Why the Discovery Matters

Historians say the achievement is less about discovering a new artifact and more about restoring knowledge.

Without context, artifacts provide limited historical insight. When reunited, they reveal burial practice, belief systems, and social organization.

The reconstruction shows how modern science can repair gaps created by early archaeological methods.

FAQs About 3D Scanning Technology

What is an Ancient Egyptian Mummy Mask?

It is a funerary covering placed over a deceased person’s face to protect identity in the afterlife and symbolize rebirth.

Why were the fragments separated?

Early excavations divided finds among sponsoring institutions, and documentation was often incomplete.

Does this physically restore the artifact?

No. The reconstruction exists digitally. The original fragments remain in their respective museums.

Could this help repatriation debates?

Yes. More precise origin identification may inform cultural heritage discussions and ownership claims.