A century-long analysis of preserved hair samples is providing rare biological evidence of how the global phaseout of leaded gasoline sharply reduced human lead exposure, reinforcing decades of environmental and medical research that link regulatory action to measurable public health gains, according to scientists involved in the study.

Table of Contents

A Unique Biological Archive Written Into Hair Samples

Unlike air filters, soil cores, or ice layers, hair samples offer something unusual: a direct biological record of environmental exposure stored in the human body itself. As hair grows, trace elements circulating in the bloodstream, including heavy metals such as lead, become embedded in the hair shaft.

Researchers analyzed thousands of hair samples collected between the late 1800s and the early 21st century. Many were preserved in museums, medical archives, and private collections, originally saved for reasons unrelated to environmental science.

“What makes hair samples powerful is their stability,” said Dr. Emily Rogers, an environmental toxicologist who contributed to the research. “Once the metal is incorporated, it stays there unless the hair is chemically treated.”

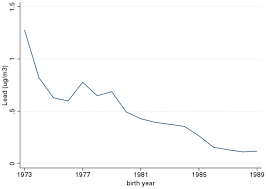

The results show a clear, long-term pattern: low lead levels in hair at the turn of the 20th century, followed by a dramatic rise beginning in the 1920s, and then a sustained decline beginning in the late 20th century.

The Rise of Leaded Gasoline and Its Invisible Fallout

Leaded gasoline was introduced commercially in the 1920s to reduce engine knocking and improve fuel efficiency. The additive, tetraethyl lead, was marketed as a technological breakthrough, despite early warnings from scientists about its toxicity.

When burned, leaded gasoline released microscopic lead particles into the air. These particles were easily inhaled or swallowed and settled into soil and household dust, especially in urban areas with heavy traffic.

By mid-century, the scale of exposure was immense. According to historical estimates from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, hundreds of thousands of tons of lead were released into the atmosphere annually during peak usage years.

“Lead exposure was not limited to factory workers or fuel handlers,” said Dr. David Rosner, a public health historian at Columbia University. “It became a background condition of everyday life.”

Hair Samples Mirror Atmospheric and Medical Data

The lead concentrations found in the hair samples closely match trends seen in atmospheric monitoring and blood lead surveys conducted decades later. Lead levels rose sharply from the 1920s through the 1960s, peaking in the postwar automobile boom.

After regulatory action began in the 1970s, hair lead levels declined steadily. By the early 2000s, average concentrations were more than 90 percent lower than their mid-century peak.

“This agreement across independent data sources strengthens confidence in the findings,” Rogers said. “Hair samples are not telling a different story. They are confirming what we suspected.”

How Scientists Analyze Hair Samples

To measure lead, researchers clean each hair sample to remove surface contamination, then dissolve it using controlled laboratory processes. Advanced instruments, such as mass spectrometers, detect trace amounts of metals with high precision.

The method allows scientists to distinguish between external contamination and lead absorbed during hair growth. That distinction is critical for accuracy.

“Modern analytical tools allow us to analyze samples that were collected generations ago,” Rogers explained. “That’s what makes retrospective studies like this possible.”

The Public Health Consequences of Lead Exposure

Medical research has firmly established that lead is a neurotoxin with no safe level of exposure. Children are particularly vulnerable because their brains are still developing.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, childhood lead exposure is associated with reduced IQ, learning difficulties, attention disorders, and behavioral problems. In adults, lead exposure increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, kidney damage, and premature death.

A landmark analysis published by the World Health Organization estimates that lead exposure accounted for more than one million deaths globally each year before major regulatory controls were in place.

Regulation and the Long Decline in Hair Sample Lead Levels

In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency began regulating leaded gasoline under the Clean Air Act in the early 1970s. The phaseout occurred gradually to allow vehicle fleets and refineries to adapt.

Other high-income countries followed similar paths, while low- and middle-income nations transitioned later. The final country to eliminate leaded gasoline did so in 2021, according to the United Nations Environment Programme.

The decline in lead levels in hair samples tracks closely with these policy timelines.

“This is one of the clearest examples of regulation producing measurable biological benefits,” said Maria Neira, director of public health at the World Health Organization.

A Global Perspective on Hair Samples and Exposure

While the overall trend is clear, researchers note regional differences. Hair samples from North America and Western Europe show earlier declines, reflecting earlier regulatory action.

Samples from parts of Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia show elevated lead levels persisting into the late 20th and early 21st centuries, consistent with later phaseouts.

“These differences reflect policy timing, not biology,” Rogers said. “They underscore the importance of global coordination in environmental health.”

Economic and Social Effects Beyond Health

The benefits of reduced lead exposure extend beyond medicine. Economists have linked declining lead levels to improved educational outcomes, increased lifetime earnings, and reduced social costs.

A World Bank analysis estimated that childhood lead exposure costs the global economy hundreds of billions of dollars annually due to lost productivity.

“These gains compound over generations,” said Neira. “The returns on prevention are enormous.”

Limitations and Scientific Caution

Researchers emphasize that hair samples are not perfect indicators of total lead exposure. Individual grooming habits, hair treatments, and occupational exposures can influence results.

The samples analyzed were also not evenly distributed across populations, with greater representation from certain regions and socioeconomic groups.

“These limitations do not negate the findings,” Rogers said. “But transparency about uncertainty is essential.”

Lessons for Modern Environmental Policy

Scientists and policymakers say the study holds lessons for today’s environmental debates, including concerns about air pollution, industrial chemicals, and emerging contaminants such as microplastics.

“The lead story shows that waiting for absolute certainty can cause lasting harm,” Rosner said. “At the same time, it shows that policy can reverse damage.”

Looking Ahead

Researchers plan to expand their work by analyzing hair samples for other pollutants, including mercury and industrial chemicals, to assess long-term exposure trends.

“Hair is an archive we are only beginning to understand,” Rogers said. “It holds clues about how today’s environment will shape future generations.”

FAQs About How the Leaded Gas Ban Changed Public Health

What makes hair samples useful for environmental research?

They preserve long-term exposure to metals and pollutants in a stable biological form.

Does lower lead in hair mean the problem is solved?

No. Legacy lead remains in soil, housing, and water systems.

Are hair samples still used today?

Yes, especially in forensic science, toxicology, and historical exposure research.