American Chestnut Comeback Plan: The American chestnut comeback plan aims to revive a functionally extinct tree that once shaped entire ecosystems, cultures, and economies across the Eastern United States. Before the blight took hold, the American chestnut was so common, so dependable, and so deeply woven into life on Native lands that many communities saw it as a partner rather than a resource. It fed families, sheltered wildlife, supported medicine-making, and shaped trade routes. Its loss left a hole in the land that people still talk about today. Now, after more than 100 years of decline, the tree may finally have a real chance at returning. Through the combined effort of scientists, tribal nations, volunteers, conservation groups, and universities, a powerful restoration movement is taking root—and the results could change the future of American forests for generations.

Table of Contents

American Chestnut Comeback Plan

The American chestnut comeback plan aims not only to revive a functionally extinct tree but to restore a piece of America’s environmental identity. This tree once fed people, shaped landscapes, supported wildlife, and rooted itself deeply in Native cultures. Its disappearance was more than a biological loss—it was a cultural and ecological wound. Today, scientists, tribes, landowners, and community members are working together to heal that wound. Through breeding, genetic engineering, traditional ecological knowledge, and public involvement, the American chestnut is finally poised for a return. If the momentum continues, future generations may once again walk beneath the towering canopy of chestnut forests and feel the presence of a long-lost relative returning home.

| Topic | Summary |

|---|---|

| What happened to the chestnut? | A blight killed about 4 billion trees from 1900–1950. |

| Why is it functionally extinct? | Trees sprout but rarely reach maturity before dying. |

| Leading restoration players | American Chestnut Foundation, universities, tribal nations. |

| Revival strategy | Hybrid breeding, genetic engineering, ecological restoration. |

| Genetic progress | Resistant trees now retain 70–85% American DNA. |

| Official source | https://acf.org |

A Tree That Once Ruled the Eastern Woodlands

For thousands of years, the American chestnut was the backbone of Eastern forests. From the Appalachian Mountains to the hardwood forests of Maine, it dominated the canopy, growing more than 100 feet tall and producing nuts by the thousands. Wildlife relied on it more than any other tree. Bears fattened themselves on chestnuts before winter. Deer and turkey counted on it as a reliable fall food. Families—Native and non-Native alike—collected chestnuts for food, flour, medicines, and trade.

In many Native cultures, the chestnut represented abundance, healing, and balance. The bark was used in teas for coughs and swelling, while the wood helped build structures, tools, and ceremonial items. The tree stood as a living partner, not just a source of material. It was a relative whose presence shaped stories, songs, journeys, and seasonal rhythms.

By the late 1800s, people considered the chestnut the perfect American tree—strong, fast-growing, productive, and generous. No one imagined it could be wiped out almost overnight.

How a Fungus Changed the Face of a Continent?

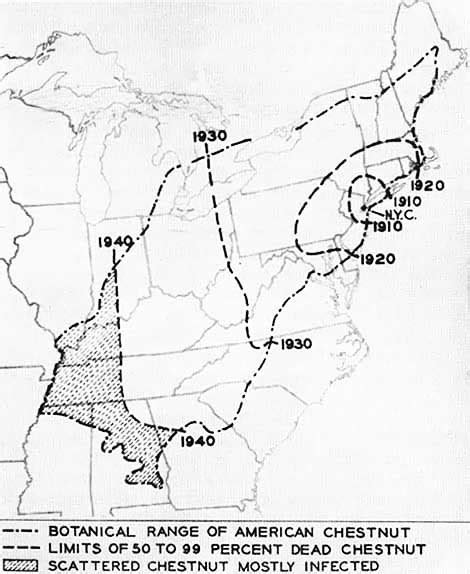

In 1904, an invasive fungus called Cryphonectria parasitica arrived on Asian trees at the Bronx Zoo. The fungus didn’t harm its original host—Asian chestnuts had evolved alongside it—but American chestnuts had no defenses.

The blight spread across the Eastern U.S. at a stunning pace. By 1950, it had killed an estimated 4 billion trees. Forests that once glowed with chestnut trunks were suddenly dark and empty. Hillsides that once fed entire villages had nothing left to offer. The ecological shock was enormous.

Even today, chestnut roots still sprout small shoots. But almost always, the fungus kills the tree before it reaches adulthood. That’s why the species is called “functionally extinct”—it is alive, but can’t complete its life cycle or contribute to the ecosystem the way it once did.

For many people, the fall of the chestnut remains one of the most heartbreaking environmental stories in American history. But the comeback plan now forming could become one of its greatest redemption stories.

American Chestnut Comeback Plan: The Modern Restoration Blueprint

Reviving the American chestnut is not a simple or quick mission. It’s a long-term restoration project grounded in science, Indigenous ecological knowledge, and community participation. The plan is made of several interconnected strategies.

Breeding for Natural Resistance

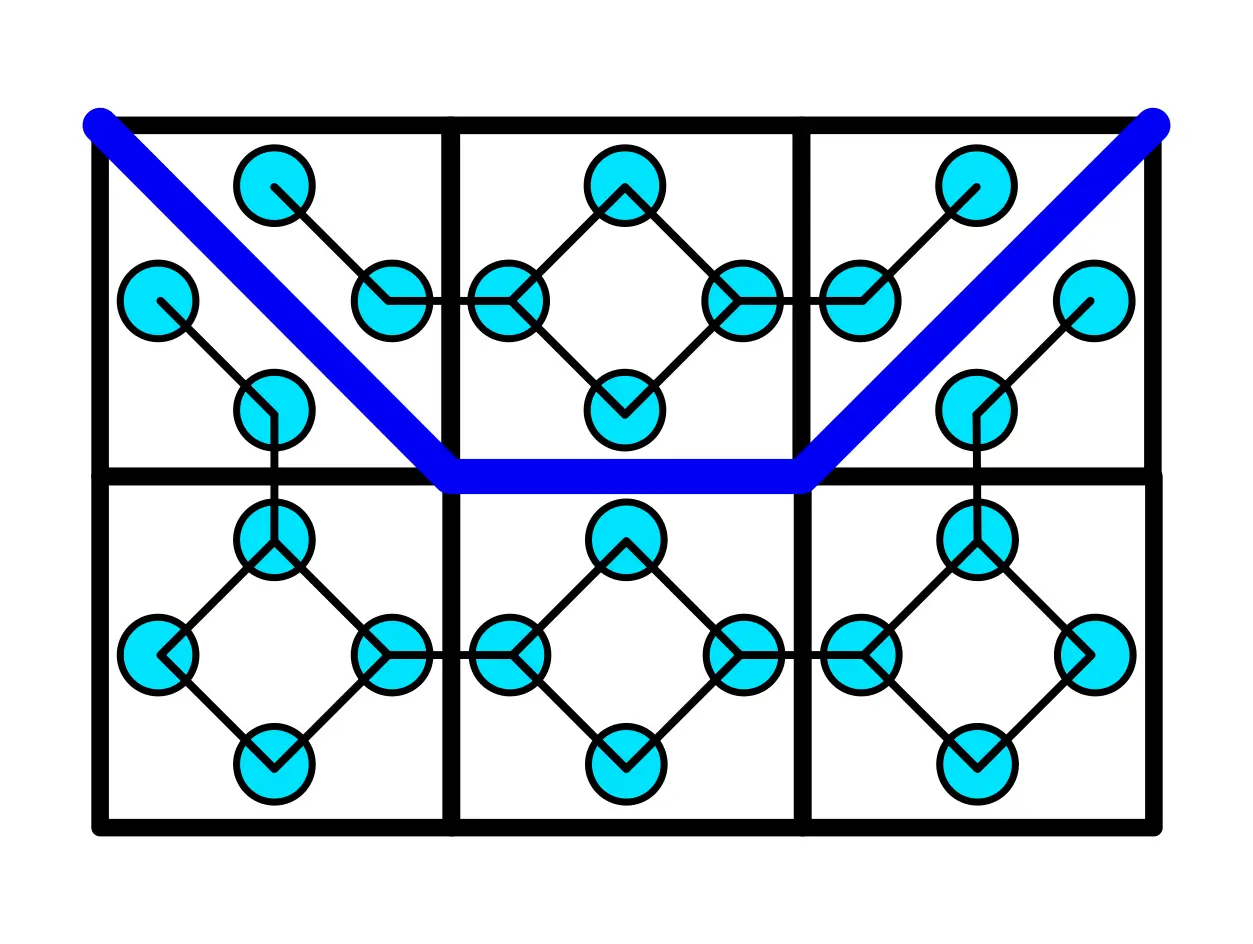

Researchers have spent decades crossbreeding American chestnuts with naturally blight-resistant Chinese chestnuts. The method is called backcross breeding. The goal is to preserve the look, growth pattern, and ecological behavior of the American tree while giving it the disease resistance it desperately needs.

This process has produced hybrids that contain about 70–85% American DNA. These trees grow tall, straight, and fast like the original species, while showing improved resistance to blight.

Field tests at universities such as Penn State, Virginia Tech, and SUNY ESF show that these hybrids survive longer, produce nuts earlier, and can coexist with local wildlife just like historic chestnut forests once did.

Genetic Engineering for Pure Chestnut Restoration

Hybrid breeding is powerful, but some scientists want to bring back a chestnut that is genetically almost identical to the original. That’s where genetic engineering enters the plan.

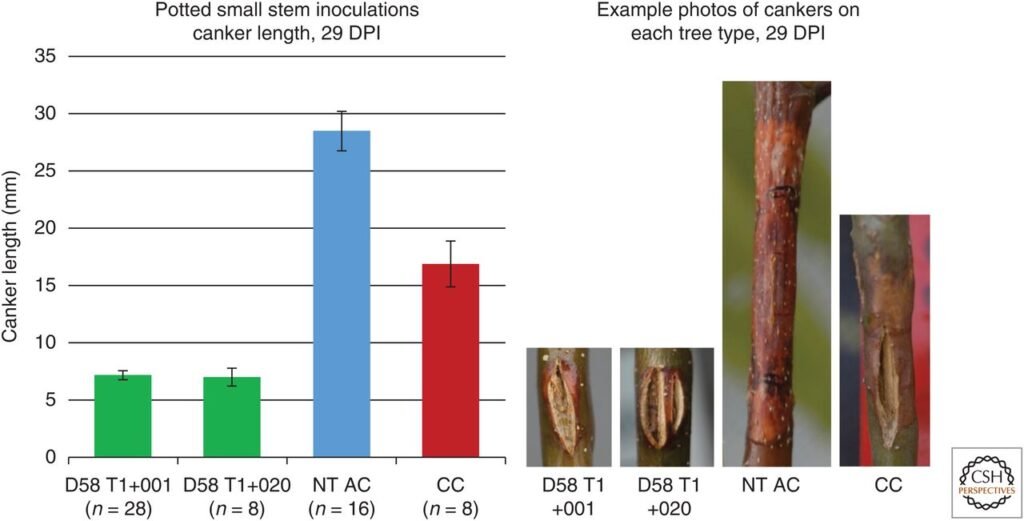

Researchers added a single wheat gene—called OxO—that helps the tree break down the acid the fungus uses to kill it. This allows the chestnut to survive infection and grow normally.

This strategy produced new varieties known as Darling 58 and Darling 54. These trees behave like pure American chestnuts in nearly every way but have the critical resistance that the original species lacked.

The USDA, EPA, and FDA are currently reviewing these trees to ensure their ecological safety. Their potential approval would open the door to major reforestation efforts across millions of acres.

Tribal Ecological Knowledge and Cultural Restoration

Many tribal nations are stepping into chestnut restoration with deep cultural purpose. Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) brings centuries of land stewardship wisdom to the restoration effort. Tribal programs incorporate:

- Seed stewardship and ceremonial planting

- Cultural burning practices

- Forest health monitoring

- Community education based on Indigenous values

For tribes whose lands historically supported chestnut forests, planting these trees is a renewal of cultural heritage. The chestnut becomes a link between past and future generations.

Why Climate Change Makes the Chestnut Even More Important?

Modern climate challenges make chestnut restoration even more timely. The species grows faster than most hardwoods—sometimes two to four feet per year—meaning it stores carbon quickly and supports new forest growth efficiently.

Because the wood is rot-resistant, the carbon stays locked away longer than in many other species. Chestnuts also stabilize soils, protect watersheds, and provide reliable mast for wildlife even as climate patterns shift.

In a warming world, restoring trees that adapt quickly, support biodiversity, and capture carbon is not just good—it’s critical.

American Chestnut Comeback Plan: Economic Benefits of a Chestnut Revival

A restored chestnut population could reshape local economies, especially in rural and tribal communities.

Chestnut nuts have a high market value, often selling for $2–$3 per pound or more. They are gluten-free, sweet, and highly nutritious, making them popular for baking and specialty foods.

The lumber industry would also benefit. Chestnut wood is lightweight, straight-grained, and naturally rot-resistant. It could revive:

- Sustainable woodworking

- Furniture-making industries

- Specialty construction

- Reforestation jobs

Seed orchards, nurseries, tribal agricultural programs, and research stations would create long-term employment and educational opportunities.

What Field Studies Tell Us So Far?

Long-term restoration plots show encouraging results. In some states, hybrid and genetically resistant trees have already reached 40–60 feet tall in under 20 years—a growth rate close to historic chestnuts.

Wildlife studies show that bear, deer, and turkey populations respond immediately to chestnut nuts when they become available. Forests with resistant chestnuts show improved biodiversity and healthier understory growth.

Perhaps most importantly, researchers have seen second-generation chestnut seedlings growing naturally in a few test sites. This means the trees are not only surviving—they’re beginning to behave like a wild population again.

For a species written off a century ago, that is monumental.

How Individuals and Communities Can Help?

Anyone can become part of the chestnut comeback. You do not need a forestry degree or acres of land to contribute.

You can join the American Chestnut Foundation, volunteer for planting events, collect local data, or educate students. Landowners can plant approved hybrids, while teachers can add chestnut lessons to environmental science classes.

Citizen science is a huge part of the mission. Reporting wild chestnut sprouts helps researchers track potential natural resistance. Even small actions help rebuild a species.

For tribal communities, restoration can connect youth to ancestral knowledge, land stewardship, and cultural pride. The chestnut becomes a teacher as much as a tree.

It’s Official: U.S. Issues Urgent Warning to Airlines Over Surging SpaceX Debris Threat

Goodwill Drops Donation Coupons — Why Shoppers Across the U.S. Are Angry

TSA’s 2026 Airport Security Change Will Alter the Screening Experience at 50 Airports