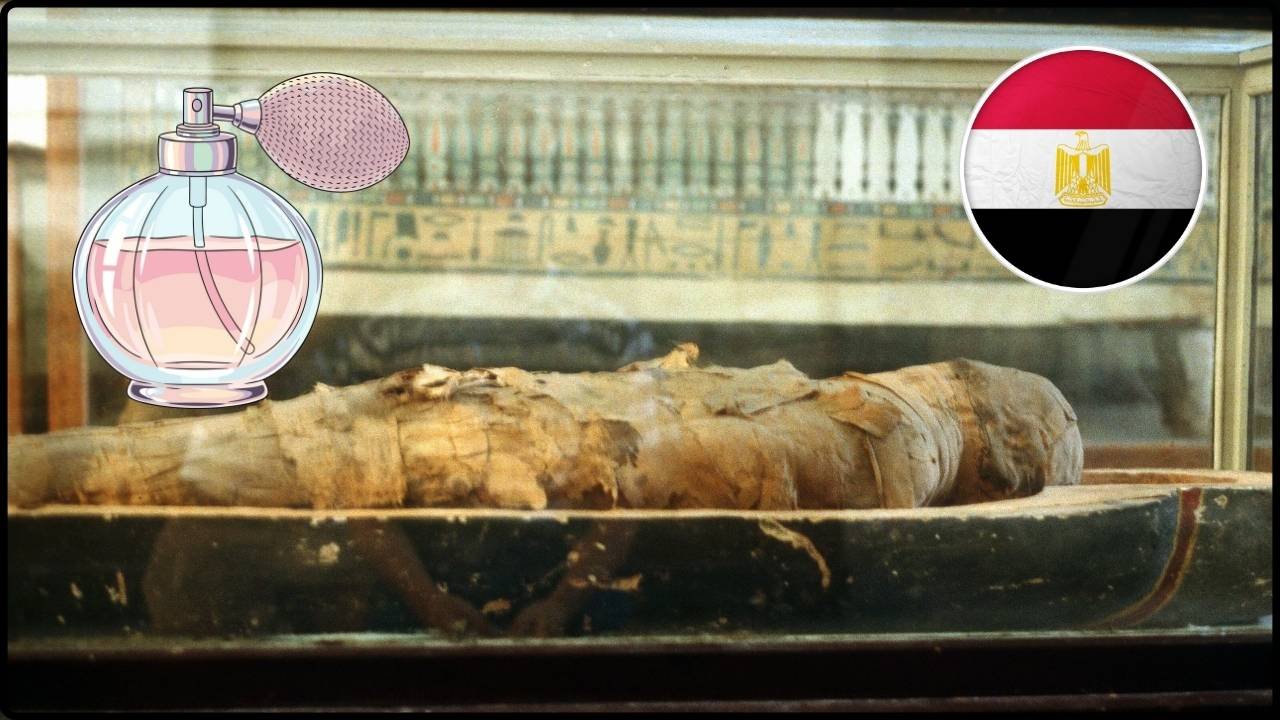

An Elephant Bone in Spain: An elephant bone in Spain could finally link Hannibal to the region, marking the first archaeological evidence that connects the legendary Carthaginian general’s war elephants directly to the Iberian Peninsula. For centuries, historians have relied on ancient texts to trace Hannibal’s path—but this new discovery offers the kind of hard, physical proof that scholars crave. Found near Córdoba in southern Spain, this ancient elephant bone is rewriting chapters of Mediterranean history, and it may finally help confirm that Hannibal’s war beasts weren’t just legend—they were stomping across Spain on their way to changing the ancient world.

Table of Contents

An Elephant Bone in Spain

One ancient elephant bone might seem small, but it carries the weight of a thousand stories. For centuries, Hannibal’s elephants lived in the realm of legend—marching through history with no trace but ink on parchment. Now, we have bones in the ground. Proof. Evidence. A bridge between past and present. Whether you’re a student, scholar, or curious traveler, this find reminds us that the stories we tell about history are always evolving—and the earth still has secrets to share.

| Feature | Details |

|---|---|

| Discovery Location | Colina de los Quemados, Córdoba, Spain |

| Item Found | Elephant right carpal (wrist) bone |

| Estimated Age | Around 2,200 years old |

| Dating Method | Radiocarbon dating and contextual analysis |

| Historical Period | Second Punic War (218–201 BC) |

| Other Artifacts Nearby | Burned structures, Iberian pottery, catapult stones |

| Significance | First physical evidence of Carthaginian elephants in Iberia |

| Reference Source | LiveScience |

Who Was Hannibal and Why Are His Elephants So Famous?

To understand why this discovery matters, let’s rewind to one of the most famous military campaigns in history.

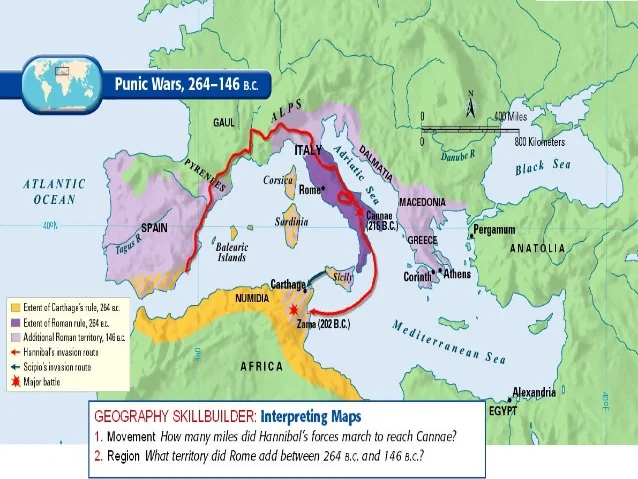

Hannibal Barca, born around 247 BC, was a Carthaginian general widely regarded as one of the greatest military strategists of all time. At the heart of his fame is his astonishing decision to march tens of thousands of troops—and dozens of elephants—across the Alps to attack the Roman Republic during the Second Punic War.

This wasn’t just a bold move; it was military theater. Elephants, rarely seen in Europe, created panic on the battlefield and functioned as living tanks—intimidating, powerful, and mobile platforms for archers and spearmen.

The story of Hannibal’s elephants has been passed down in ancient Roman texts, particularly by Polybius and Livy. But up until now, there’s been no physical proof that these elephants were ever stationed in Spain, where Hannibal’s campaign began.

That just changed.

What Exactly Was Found?

In 2019, archaeologists excavating the ancient settlement of Colina de los Quemados, located near the Guadalquivir River in Córdoba, unearthed a small but crucial find: a right carpal bone from an elephant. At first glance, it may not have looked like much. But this single bone—about the size of a baseball—could be the missing puzzle piece in proving that Hannibal’s elephants were part of his Spanish operations.

Researchers used radiocarbon dating, stratigraphy, and ceramic analysis to date the bone to between 218 and 201 BC—precisely the timeframe of the Second Punic War.

Nearby, they also found catapult stones, burnt remains of ancient buildings, and locally produced Iberian pottery, all consistent with the aftermath of a military siege. Together, this evidence supports the theory that the elephant was not part of a zoo or parade—it was involved in battle.

Spain: The Launchpad of Hannibal’s War Machine

Before Hannibal crossed the Alps, he spent years in Iberia, establishing a strong military base. Carthage had previously colonized large parts of Spain, and Hannibal took over command of these territories after his father, Hamilcar Barca, died.

From his base in Cartago Nova (modern Cartagena), Hannibal:

- Conquered rebellious Iberian tribes

- Strengthened trade and supply routes

- Trained a new generation of Carthaginian and Iberian troops

- Stockpiled resources—including elephants

Spain wasn’t just a pit stop. It was the foundation of Hannibal’s entire campaign against Rome.

Until now, we’ve only had textual records of this phase. But this elephant bone anchors those stories in the dirt, giving us something tangible to tie to his Iberian presence.

War Elephants: More Than Just Brute Force

Let’s talk strategy.

War elephants weren’t just exotic showpieces. In ancient warfare, they played a crucial psychological role. Most soldiers had never seen anything like them. They could break enemy lines, scatter cavalry, and intimidate foot soldiers. They also served as platforms for archers and javelin throwers.

Hannibal’s elephants were likely North African forest elephants—now extinct—smaller and more agile than their Asian or savannah cousins. These elephants were around 7–8 feet tall, making them easier to maneuver through rough terrain but still terrifying to unprepared soldiers.

Their utility, however, had limits. Many didn’t survive the harsh journey over the Alps, and in later battles, trained Roman forces learned to counter them using flaming pigs (yes, really), spears, and flexible formations.

But during the early stages of Hannibal’s campaign, especially in Spain, they were essential.

Why An Elephant Bone in Spain Discovery Matters to Historians?

Until now, much of Hannibal’s Iberian strategy has been reconstructed from Roman historians—who were his enemies. These accounts often leaned toward propaganda, portraying Hannibal as a cruel and cunning invader.

This discovery flips the script.

Archaeologist Dr. María Dolores Camalich, who worked on the Córdoba dig, explained in a statement:

“For the first time, we have physical evidence that ties war elephants to an actual battlefield in Iberia. This is crucial not only for understanding Hannibal but for understanding how Carthage operated as a military power.”

It also suggests that:

- Carthage’s control over Iberia was deeper than previously thought

- Hannibal likely used elephants not just for show but in actual battles within Spain

- Spanish archaeological sites may hold more undiscovered evidence of Punic military infrastructure

Connecting Past and Present: Cultural and Educational Value

Why should modern readers—especially students, tourists, and history buffs—care about a dusty elephant bone?

Because this is living history.

- For educators, it provides a tactile example of ancient military logistics.

- For Spanish citizens, it highlights the country’s crucial role in Mediterranean history.

- For tourists, it boosts historical tourism in Andalusia, where you can now literally walk where Hannibal’s elephants once roamed.

- For students, it’s proof that history isn’t just in books—it’s beneath your feet.

Teachers can now build lesson plans around this discovery, from classroom reenactments to interactive timelines of the Punic Wars.

Did You Know? Surprising Facts About Hannibal’s Campaign

- Only one elephant survived the full journey into Italy: Hannibal’s personal elephant, named Surus, meaning “The Syrian.”

- Over 38,000 troops and 8,000 cavalry joined Hannibal’s march from Spain into Italy.

- Carthage was one of the wealthiest cities in the ancient world, thanks to trade across Africa, Spain, and the Mediterranean.

An Elephant Bone in Spain: What’s Next for Researchers?

Now that they’ve found one elephant bone, archaeologists are going back to the Colina de los Quemados site for more.

Using ground-penetrating radar, digital modeling, and AI-assisted scanning, they’re hoping to uncover:

- Additional elephant remains

- Punic-era weapons

- More fortified structures that confirm the location as a Carthaginian military outpost

There’s also increased funding interest from universities across Spain and Italy, aiming to digitize and model Hannibal’s routes across the peninsula.

This discovery could open up a new chapter in ancient Mediterranean archaeology.

Archaeologists Discover a Rare Lead Pipeline in Petra’s Ancient Aqueduct

A Giant Medieval Ship Emerges From the Seafloor in Denmark, Stunning Archaeologists

What Antarctica Looked Like Before Ice — And the Civilization Some Scientists Are Questioning