Rare Form of Dwarfism: In a discovery that’s shaking up archaeology and genetics, ancient DNA reveals a rare form of dwarfism in a 12,000-year-old teen — rewriting what we know about early human health and social care. Unearthed from the famous Grotta del Romito cave in southern Italy, this teenager — known to scientists as Romito 2 — may have faced significant physical challenges, but her survival tells an incredible story of prehistoric compassion.

Her skeleton was first found in 1963, but it wasn’t until 2023–2025 that DNA technology became advanced enough to uncover the truth hidden in her bones. Researchers from the University of Vienna, Sapienza University of Rome, and the University of Liège teamed up to decode her genetic story, and what they found was astonishing: Romito 2 had acromesomelic dysplasia, Maroteaux type (AMDM) — an extremely rare, inherited form of dwarfism that drastically stunts bone growth in the limbs. This is now officially the earliest known case of a human genetic disorder diagnosed via DNA, and it challenges modern assumptions about disability, survival, and support in early societies.

Table of Contents

Rare Form of Dwarfism

The story of Romito 2 — a teenage girl who lived 12,000 years ago with a rare genetic disorder — is more than a scientific milestone. It’s a story about humanity, resilience, and care that transcends time. Her tiny frame may have carried a heavy genetic burden, but it also carried a legacy: one that proves early humans were not just survivors — they were caretakers, lovers, and protectors of even their most vulnerable. And now, through the magic of modern science, she lives again — not in flesh, but in fact.

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| Name | Romito 2 |

| Age at Death | Teenager (approx. 12–13 years old) |

| Condition | Acromesomelic dysplasia, Maroteaux type (AMDM) |

| Genetic Cause | Mutation in both copies of the NPR2 gene |

| Height | Approx. 3 ft 7 in (110 cm) |

| Burial Site | Grotta del Romito, Calabria, Italy |

| Year Found | 1963 (DNA tested in 2023–2025) |

| Study Published In | New England Journal of Medicine |

| Lead Researchers | Dr. Adrian Daly, Dr. Ron Pinhasi |

What Exactly is Acromesomelic Dysplasia?

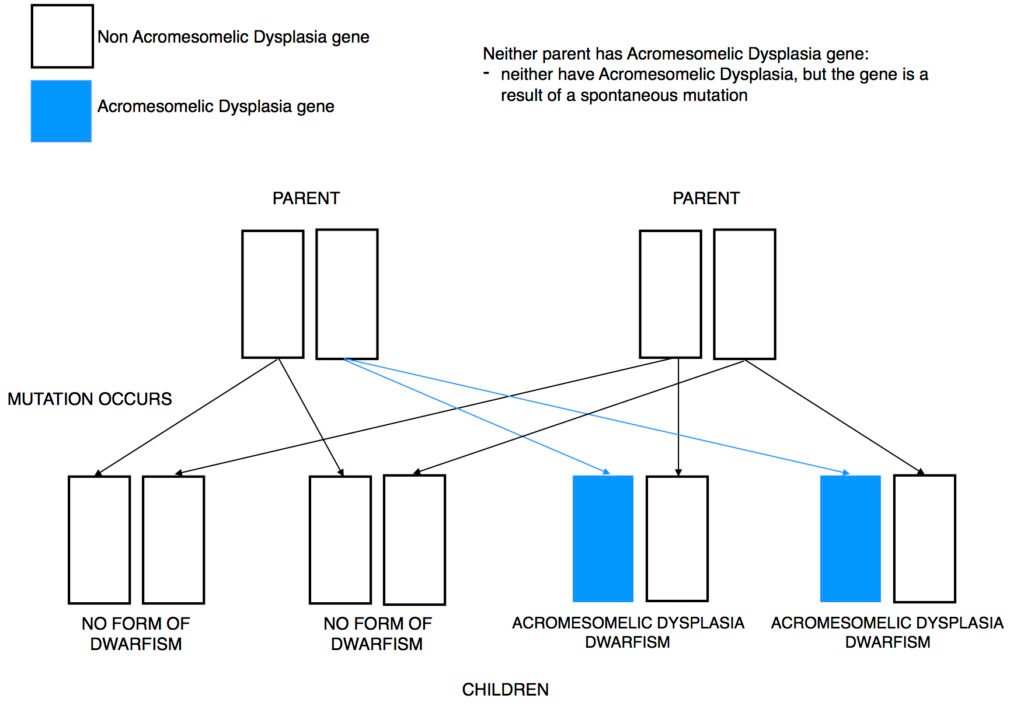

Let’s make this real simple. Acromesomelic dysplasia (AMDM) is a rare disorder that affects bone development. Kids born with it end up having extremely short arms and legs, while their spine and head often grow more normally. That means they don’t just look short — their whole physical range is different.

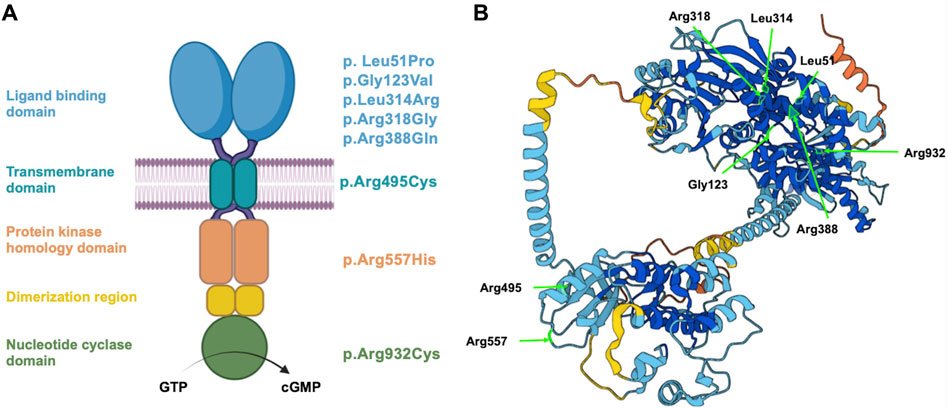

This condition is genetic — meaning it’s inherited. You need to get the faulty gene from both parents to have the condition, and that’s exactly what happened with Romito 2. The gene in question is called NPR2, and when it’s not working right, it throws off the entire process of how bones grow, particularly in the long bones of your arms and legs.

People living with AMDM today have normal intelligence and can live full lives, but they often face joint problems, limited mobility, and require surgeries, therapy, or adaptive tools — things ancient people didn’t have.

And here’s the kicker: AMDM is incredibly rare, with an estimated frequency of 1 in 1 million births globally. Finding this in a prehistoric human? Practically unheard of — until now.

The Discovery of Rare Form of Dwarfism: More Than Just Bones

Romito 2’s remains were found lying on her left side, legs tucked in, and arms folded — an intentional burial posture suggesting care and ceremony. She was laid next to Romito 1, an adult female believed to be her mother or close relative.

Researchers took DNA from Romito 2’s petrous bone — the densest part of the human skull and one of the best spots for finding preserved genetic material in ancient remains. This DNA was then analyzed using whole genome sequencing and compared with modern genetic databases.

Bingo. They found homozygous mutations in the NPR2 gene — meaning both gene copies had the AMDM mutation. Her relative, Romito 1, had just one mutated gene, suggesting she was a carrier who may have had mild short stature herself.

The study appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine and was verified by teams specializing in ancient genomics, skeletal analysis, and clinical genetics.

What Life Was Like 12,000 Years Ago With A Rare Form of Dwarfism?

Let’s paint the scene: It’s the end of the Ice Age, around 10,000 BCE. Southern Italy is lush with vegetation, herds of wild animals, and small groups of humans trying to make it in a tough world. People hunted with spears, gathered fruits and nuts, and relied on teamwork for survival.

In this kind of setting, someone like Romito 2 — with short limbs and likely reduced physical stamina — wouldn’t have made it on her own. She couldn’t hunt, build shelters, or walk long distances easily. But she lived into her teens. That means her tribe didn’t just tolerate her — they actively supported her.

This flies in the face of outdated beliefs that prehistoric life was solely about strength and speed. It suggests early humans had compassion, care systems, and saw value in every member, even those who couldn’t contribute in typical ways.

“Romito 2 is a powerful example of prehistoric caregiving,” said Dr. Ron Pinhasi. “Her survival reflects strong social bonds and perhaps a cultural value placed on empathy.”

How Rare Is This Rare Form of Dwarfism Really?

Let’s put this into perspective with known forms of dwarfism today:

| Type of Dwarfism | Cause | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Achondroplasia | FGFR3 gene mutation | 1 in 25,000 |

| Pseudoachondroplasia | COMP gene mutation | Rare |

| Acromesomelic dysplasia (AMDM) | NPR2 gene mutation | ~1 in 1,000,000 |

The fact that scientists not only identified AMDM in a 12,000-year-old human, but confirmed the genetic cause is nothing short of revolutionary in the field of paleogenetics.

What the Burial Tells Us?

Romito 2 wasn’t buried in a shallow, careless grave. Her burial at Grotta del Romito was:

- Intentional

- Respectful

- Communal

She was positioned in a way that matches other known cultural burial styles of the time, and her companion was placed nearby in a similar pose. This tells us that ritual and remembrance were important to these people.

Grotta del Romito itself is a well-known archaeological site, containing:

- Eight burial pits

- Cave engravings of wild cattle (aurochs)

- Tools and hearths from the Upper Paleolithic period

This wasn’t just a resting place — it was a community hub and sacred space.

How Ancient DNA Analysis Works?

Extracting ancient DNA (aDNA) is no walk in the park. The older the bones, the harder it is to get readable sequences. Factors like temperature, soil acidity, microbial activity, and time can all degrade genetic material.

Researchers used:

- Ultraclean labs

- Next-gen sequencing

- Bioinformatics software

By mapping the data against modern reference genomes, scientists can identify mutations even if the DNA is fragmented. In Romito 2’s case, they zeroed in on exons — the protein-coding parts of the gene — where disease-causing mutations usually live.

Lessons for Today: Science Meets Humanity

This discovery isn’t just academic. It touches on some big themes:

- Genetic counseling: Understanding ancient gene mutations helps doctors today predict inheritance patterns and offer guidance to families.

- Disability advocacy: Romito 2’s story shows that people with disabilities were valued even before written history.

- Human resilience: Despite a major physical condition, this teen girl lived long enough to form bonds, participate in culture, and be remembered.

It’s also a reminder that science isn’t just about numbers — it’s about people. People with names, families, and struggles. And thanks to technology, we’re now able to hear their stories again.

Fungus-Based Insecticides — Why Scientists Say They Could Be the Future

How Supermassive Black Holes in the Early Universe Grew Inside Cosmic “Cocoons”

Fewer Than 20 People Will See This Rare Solar Eclipse Over Antarctica