Complex Structure Inside a Kingfisher Feather: and this breakthrough is reshaping how scientists, engineers, and educators understand color itself. At first glance, a kingfisher’s bright blue feathers might seem like simple pigmentation. But modern X-ray imaging reveals something much deeper: a finely tuned nanostructure inside each feather that manipulates light with remarkable precision. This discovery isn’t just fascinating biology — it’s cutting-edge physics, materials science, and sustainable innovation all rolled into one. If you’ve ever watched a kingfisher zip across a river in the American Midwest or along a Florida shoreline, you’ve seen that electric flash of blue. It looks painted on — bold, vivid, almost glowing. But here’s the twist: there is no blue pigment in those feathers. Instead, the color is produced by microscopic physical structures that bend and scatter light. Thanks to advanced imaging methods like synchrotron X-ray scanning, researchers now understand how that works in extraordinary detail.

Table of Contents

Complex Structure Inside a Kingfisher Feather

X-Ray Imaging Shows the Complex Structure Inside a Kingfisher Feather has transformed what we know about color in the natural world. Through synchrotron imaging and optical modeling, scientists uncovered a nanoscale keratin-air structure responsible for the bird’s iconic blue glow. This discovery bridges biology, physics, engineering, sustainability, and cultural preservation. It offers practical solutions for eco-friendly manufacturing and inspires next-generation photonic materials. Nature’s design remains one of the most advanced engineering systems on Earth.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Main Discovery | Blue color comes from nanoscale keratin-air structures, not pigment |

| Imaging Technology | Synchrotron X-ray imaging |

| Nanostructure Size | ~150–200 nanometers spacing |

| Scientific Principle | Structural coloration via light interference |

| Research Institutions | Northwestern University, Argonne National Laboratory |

| Industry Applications | Sustainable textiles, optics, solar tech, anti-counterfeit materials |

| Career Relevance | Materials science, photonics, environmental engineering |

| Salary Range (USA) | Materials scientists median salary: $104,100 (BLS.gov) |

Understanding Complex Structure Inside a Kingfisher Feather

Let’s make this simple.

Most animals get their colors from pigments. Pigments are chemicals that absorb some colors of light and reflect others. That’s how we get red apples, yellow bananas, and brown eyes.

But the kingfisher? It plays by different rules.

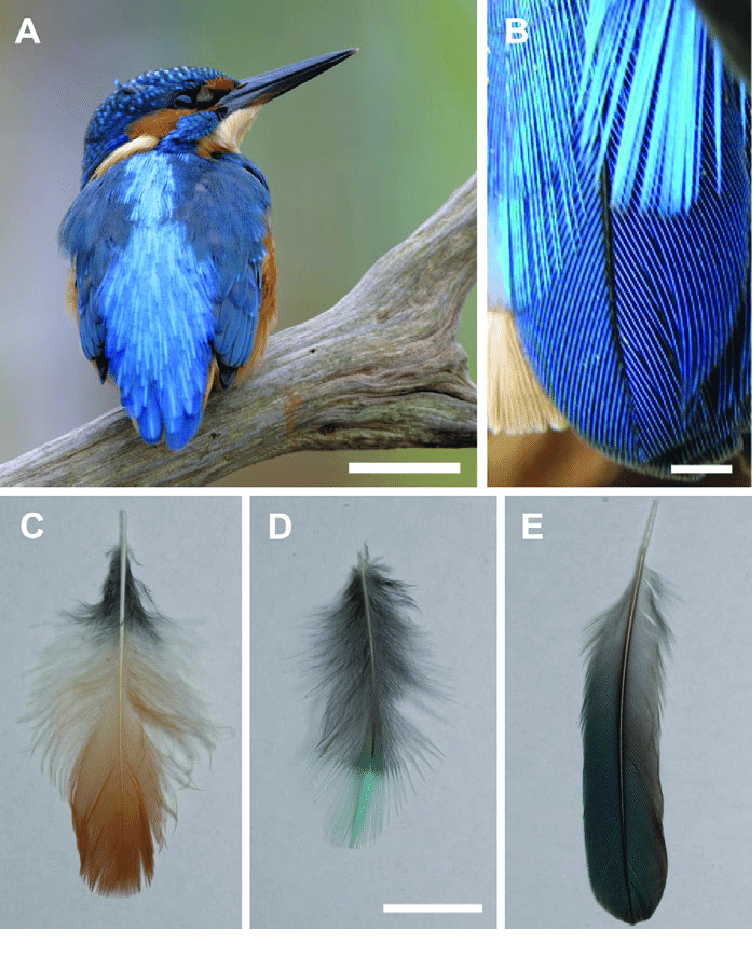

Its blue feathers are an example of structural coloration — a phenomenon where color is created by the way microscopic structures interact with light. These structures are made of keratin (the same protein found in human hair and nails) arranged in a sponge-like network with tiny air pockets.

The spacing between these structures is about 150 to 200 nanometers — which is smaller than the width of a human hair by a factor of 500. Because blue light has wavelengths around 450–495 nanometers, this nanoscale spacing selectively reflects blue wavelengths while scattering others.

In simple terms: the feather doesn’t contain blue dye. It’s engineered by nature to reflect blue light.

The Role of Synchrotron X-Ray Imaging

To uncover this hidden architecture, researchers turned to synchrotron X-ray imaging, a highly advanced technique available at national laboratories such as the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, synchrotron facilities generate X-rays that are billions of times brighter than those used in medical imaging. That intensity allows scientists to:

- Capture 3D nanoscale structures

- Analyze internal feather architecture without cutting it open

- Map the exact arrangement of keratin and air

This type of imaging is essential because traditional microscopes cannot penetrate deeply enough or provide sufficient resolution.

The process typically involves placing a feather sample in a beamline, rotating it incrementally, and capturing thousands of cross-sectional images. These images are then reconstructed into a detailed 3D model using computational software.

For professionals in materials science or optical engineering, this level of structural mapping is comparable to reverse-engineering a photonic crystal.

The Physics Behind the Complex Structure Inside a Kingfisher Feather

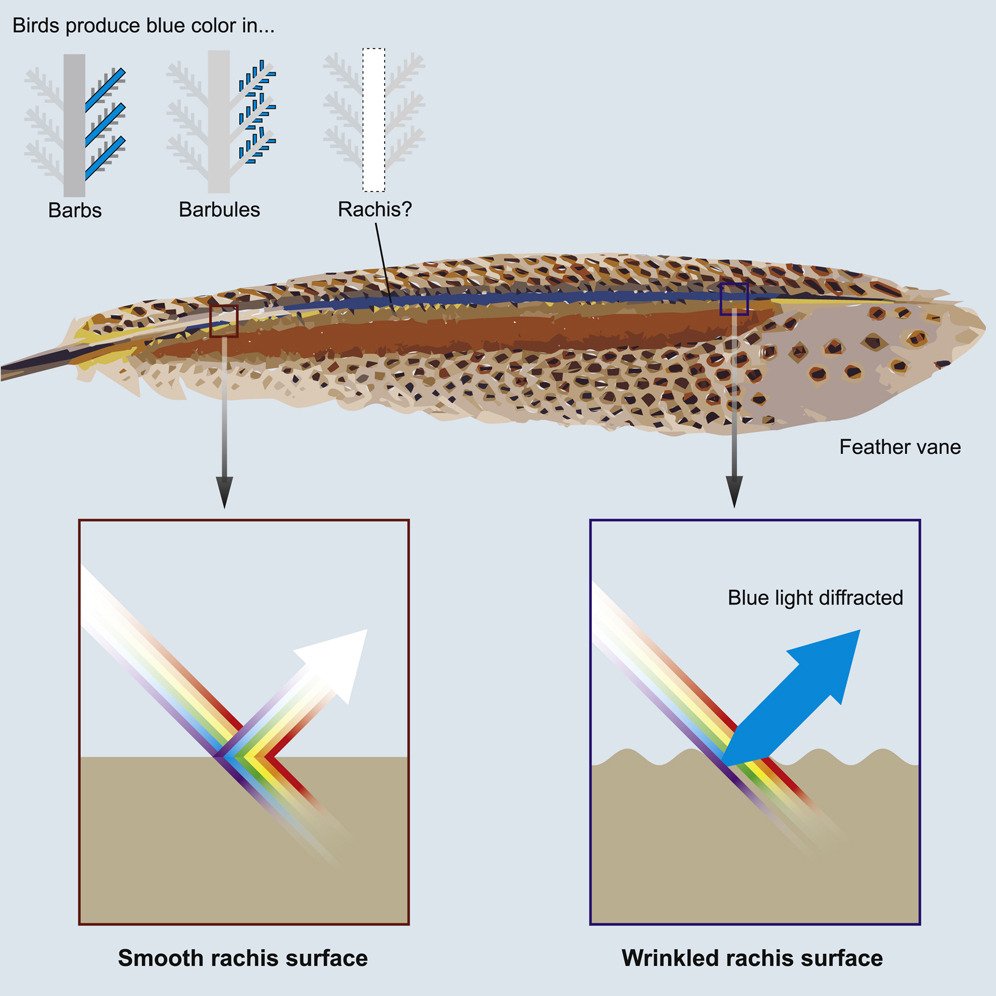

The science involved centers on constructive interference and Bragg scattering.

When light waves encounter periodic structures — like the repeating keratin-air patterns in the feather — certain wavelengths reinforce each other. Blue light wavelengths align perfectly with the nanostructure spacing, creating strong reflection.

The refractive index of keratin is approximately 1.55, while air is 1.0. This contrast enhances scattering effects.

From an optical modeling standpoint:

- The feather functions as a quasi-ordered photonic structure.

- Scattering occurs isotropically but peaks in the blue spectrum.

- Slight irregularities reduce iridescence, giving kingfishers a matte yet vibrant blue rather than a rainbow shimmer like some butterflies.

This distinction is important. Unlike peacock feathers, which show iridescence (color shifts dramatically by angle), kingfisher feathers maintain a more stable hue due to the semi-random nature of their nanostructure.

Why This Complex Structure Inside a Kingfisher Feather Discovery Matters for Sustainability?

Here’s where things get practical.

The global textile industry is one of the largest sources of water pollution due to chemical dyes. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency reports significant environmental impact from dye runoff, including contamination of freshwater ecosystems.

Imagine producing color without chemicals — purely through engineered structure.

By mimicking kingfisher feather nanostructures, manufacturers could:

- Eliminate toxic dye waste

- Reduce water consumption

- Create longer-lasting, fade-resistant colors

Researchers in biomimicry are already exploring synthetic materials that replicate these structural principles. Companies investigating sustainable textiles closely monitor developments in photonic materials research.

For product designers, this is a major opportunity. Consumers increasingly demand eco-conscious products. Structural color technologies may become a competitive advantage.

Applications in Optics and Engineering

Beyond textiles, this research influences high-tech sectors.

Photonic crystals — materials that control the flow of light — are used in:

- Fiber optic communication

- LED displays

- Laser technologies

- Solar panels

The nanoscale organization found in kingfisher feathers mirrors some artificial photonic crystal designs but is achieved naturally at room temperature without expensive fabrication processes.

Engineers are studying how biological systems self-assemble such precise nanostructures. If we can replicate nature’s manufacturing efficiency, we could significantly reduce production costs in optical materials.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, physicists and materials scientists continue to experience strong job demand in emerging technology sectors. Research inspired by natural photonic systems feeds directly into these career pathways.

Implications for Art Conservation and Cultural Heritage

Structural coloration research also supports conservation science.

In historical Chinese decorative art known as Tian-tsui, actual kingfisher feathers were used in jewelry because of their lasting blue brilliance. Museums such as the Smithsonian National Museum of Asian Art rely on non-destructive imaging techniques to study and preserve these artifacts.

Understanding feather nanostructure helps conservators determine:

- How light exposure affects degradation

- Optimal humidity storage levels

- Best restoration practices

X-ray imaging ensures preservation without damaging priceless artifacts.

Step-by-Step: How Scientists Conduct Feather Imaging Research

- Specimen Selection

Researchers obtain ethically sourced feather samples, often from natural molts. - Stabilization

Samples are conditioned to avoid structural collapse under X-ray exposure. - Beamline Setup

At synchrotron facilities, precise calibration ensures nanoscale resolution. - Tomographic Scanning

Thousands of rotational scans generate cross-sectional images. - Digital Reconstruction

Advanced algorithms compile 3D visualizations. - Optical Simulation Modeling

Scientists simulate light interactions to confirm structural color behavior. - Peer Review and Publication

Findings undergo scientific validation through journals and institutional review.

This rigorous workflow ensures reliability and reproducibility.

Career and Educational Opportunities

Students interested in this field should focus on:

- Physics

- Materials science

- Nanotechnology

- Environmental engineering

- Computational modeling

Median salaries in the U.S. reflect strong demand:

- Materials Scientists: $104,100

- Physicists: $155,680

- Environmental Engineers: $96,820

These figures come from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Interdisciplinary education is key. Combining biology with engineering opens doors to biomimetic innovation.

Broader Ecological Perspective

Understanding feather structure also enhances ecological knowledge.

Color plays roles in:

- Camouflage

- Mate selection

- Species recognition

Because structural coloration does not fade as easily as pigment, it may offer evolutionary advantages. Stable coloration could support consistent signaling within species populations.

Studying how these nanostructures develop genetically may also shed light on avian evolutionary biology.

Advanced Scanning Reunites Pieces of an Ancient Egyptian Mask

Ancient Deer Skull Headdress in Germany Hints at Early Cultural Connections

Aerial Survey Uncovers a Previously Unknown Theater in Ancient Rome