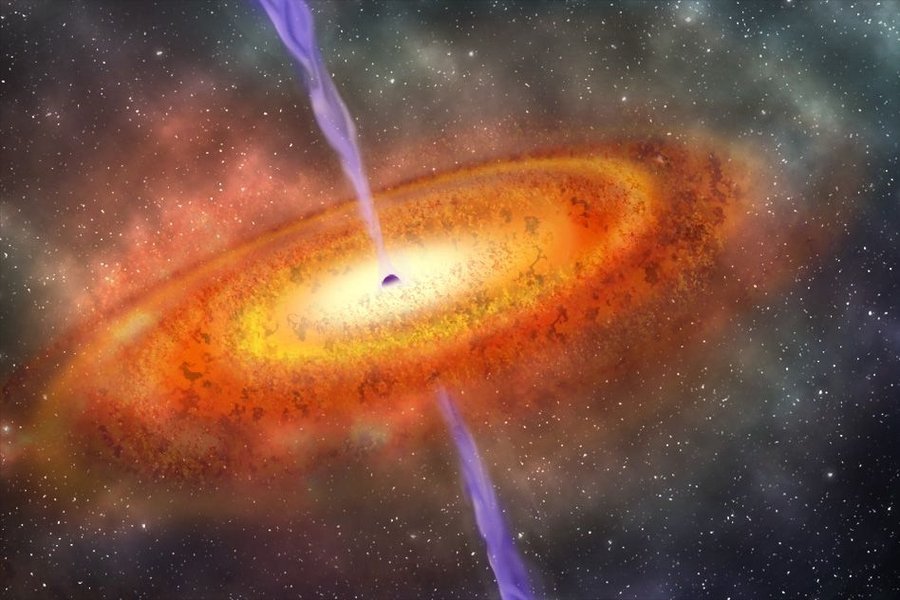

Astronomers have uncovered evidence that Supermassive Black Holes in the early universe grew inside dense cosmic “cocoons” of gas, allowing them to gain mass rapidly while remaining largely hidden from view. The finding helps resolve a long-standing mystery: how black holes became enormous within the universe’s first billion years, far earlier than classical growth models predicted.

Table of Contents

Supermassive Black Holes

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Growth environment | Dense gas cocoons |

| Time period | First billion years after Big Bang |

| Visibility | Weak X-ray and radio emission |

| Scientific impact | Revises early black hole growth models |

The Long-Standing Mystery of Early Supermassive Black Holes

For decades, astronomers have known that nearly every large galaxy contains a Supermassive Black Hole at its center. In the modern universe, these objects typically grow slowly by pulling in surrounding gas, dust, and stars over billions of years.

The puzzle emerged when astronomers began discovering extremely distant quasars—bright beacons powered by black holes—existing when the universe was less than one billion years old. Some of these black holes already appeared to contain hundreds of millions or even billions of times the mass of the Sun.

Under standard assumptions, there simply should not have been enough time for such massive objects to form.

This discrepancy led scientists to question whether their understanding of black hole growth was incomplete, or whether entirely new physics might be required.

A New Clue Hidden in Red Light

The breakthrough came from observations of faint, compact objects that appear unusually red in deep infrared images of the early universe. These sources are small, bright, and abundant, yet lack many of the signatures expected from normal galaxies.

Astronomers initially debated their identity. Some suggested they were compact starburst galaxies. Others proposed they were exotic stellar systems or unusually dense clusters of stars.

A closer analysis of their light, however, revealed features more consistent with accreting black holes than with stellar populations.

The key insight was not just what was visible—but what was missing.

Why These Objects Were So Hard to See

In the modern universe, actively feeding black holes often announce themselves through intense X-ray and radio emission. Many of these distant red objects showed little or none of that radiation.

Rather than weakening the black hole interpretation, this absence became central to a new explanation.

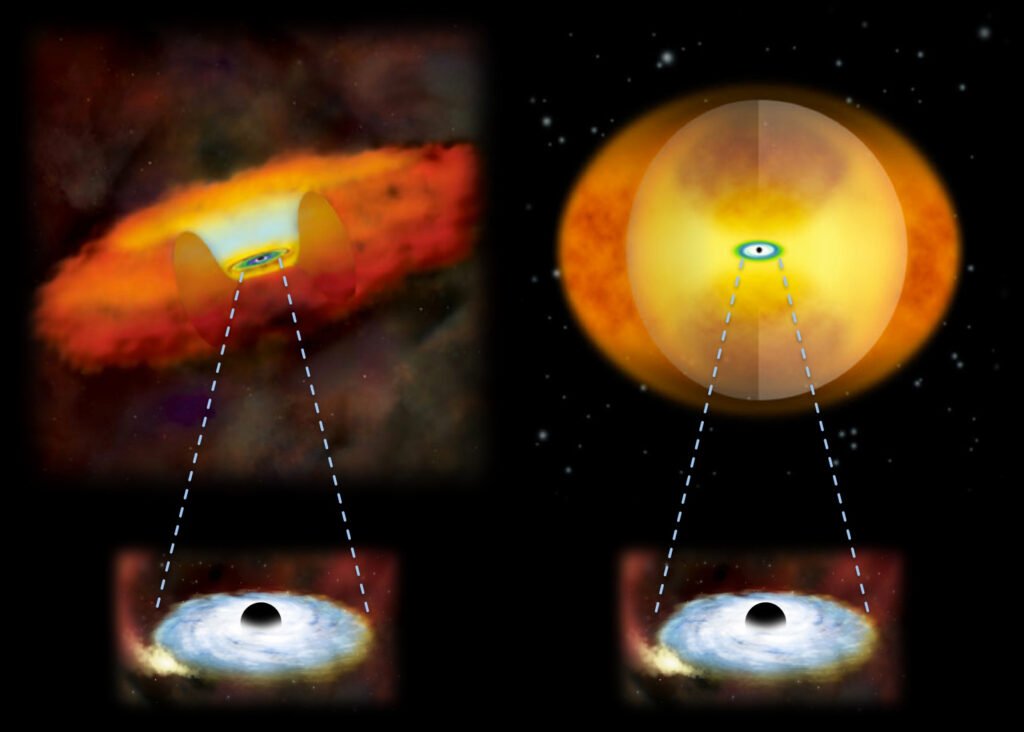

Researchers concluded that these young Supermassive Black Holes were likely embedded within thick cocoons of gas and ionized particles. These cocoons absorb high-energy radiation and re-emit it at longer, redder wavelengths.

As a result, the black holes appear faint or invisible in X-ray surveys but glow softly in infrared light.

This explains why earlier telescopes, which were less sensitive to infrared wavelengths, failed to detect large populations of growing black holes in the early universe.

How Cosmic Cocoons Enable Rapid Growth

The cocoon model offers a compelling solution to the early growth problem.

Under normal conditions, as a black hole feeds, the radiation it produces pushes back against incoming material. This process limits how quickly the black hole can grow.

Inside a dense cocoon, that balance changes.

The surrounding gas traps radiation, reducing the outward pressure that would otherwise halt accretion. Gas continues to fall inward, allowing the black hole to grow efficiently and steadily.

This process does not require exotic physics or extreme assumptions—only environments rich in gas, which were common in the early universe.

Revising Black Hole Mass Estimates

Earlier studies often assumed that the brightness of these red objects directly reflected the mass of the black holes powering them. Under that assumption, many appeared extraordinarily massive.

New modeling suggests those estimates were inflated.

When the effects of scattering, absorption, and re-emission by the cocoon are taken into account, the black holes appear significantly smaller—often millions rather than billions of solar masses.

Even so, they remain firmly in the category of Supermassive Black Holes, and their rapid growth rates remain remarkable.

This recalibration reduces the tension between observation and theory without diminishing the scientific importance of the discovery.

How Astronomers Reconstruct Invisible Objects

Because black holes emit no light themselves, astronomers rely on indirect methods to study them.

These include:

- Analyzing how surrounding gas emits light at different wavelengths

- Measuring spectral line widths to estimate motion near the black hole

- Modeling how radiation interacts with dense environments

By combining multiple lines of evidence, researchers can infer the presence, mass, and growth rate of black holes even when they are heavily obscured.

The cocoon model emerged not from a single observation, but from the convergence of many independent measurements.

How This Fits with Other Black Hole Formation Theories

The cocoon growth phase does not replace other theories of black hole formation. Instead, it complements them.

Some models propose that early black holes formed from the collapse of massive stars. Others suggest they formed directly from enormous clouds of gas. Mergers of smaller black holes may also have played a role.

The cocoon scenario focuses on how black holes grew, rather than how they were initially born.

It suggests that regardless of their origin, many early Supermassive Black Holes likely experienced a heavily obscured growth phase before becoming the luminous quasars seen later in cosmic history.

What This Discovery Does Not Mean

Researchers emphasize several important clarifications:

- It does not imply that all early galaxies contained massive black holes

- It does not eliminate the need for other growth or formation mechanisms

- It does not suggest that black holes violate known physical laws

Instead, it highlights how extreme environments can alter the appearance and behavior of otherwise familiar objects.

Broader Implications for Cosmic Evolution

Supermassive black holes influence their host galaxies by heating gas, regulating star formation, and shaping large-scale structure.

If many early black holes grew while hidden inside cocoons, it suggests the early universe may have been far more active than previously believed.

This has implications for:

- When the first galaxies stabilized

- How early stars formed and died

- How matter was redistributed across cosmic scales

Understanding these early phases helps astronomers build more accurate models of how the universe evolved into its present form.

What Comes Next After Supermassive Black Holes

Future observations will aim to determine how common the cocoon phase was and how long it typically lasted.

Astronomers will also look for transitional objects—black holes emerging from cocoons and beginning to shine as classical quasars.

Each new dataset will refine the picture of how the universe’s most massive objects came to be.

Final Paragraph

The discovery of cocooned growth offers a missing chapter in the story of Supermassive Black Holes, showing how they could grow rapidly without revealing themselves. As observations improve, astronomers expect this hidden phase to become a cornerstone of early universe research rather than an exception.

FAQs About Supermassive Black Holes

What are Supermassive Black Holes?

They are black holes containing millions to billions of times the mass of the Sun, typically found at the centers of galaxies.

Why is the cocoon phase important?

It explains how black holes could grow rapidly while remaining difficult to detect.

Does this change current physics?

No. It refines existing models by accounting for extreme environments in the early universe.