A new wave of scientific studies examining Human Lifespans suggests people may be capable of living significantly longer than once believed. Researchers analyzing decades of international twin data report that genetics plays a larger role in determining lifespan than earlier estimates indicated, reshaping long-standing assumptions about aging, disease risk, and the biological limits of human life.

Table of Contents

Human Lifespans May Be Longer Than Previously Estimated

| Key Fact | Detail/Statistic |

|---|---|

| Genetic influence | About 50–55% of lifespan variation linked to heredity |

| Previous estimate | Earlier research suggested roughly 20–25% genetic influence |

| Lifespan ceiling | Some scientists place biological limit near 120–150 years |

Scientists expect further genome research and long-term population studies to refine estimates in coming decades. For now, the Human Lifespans findings suggest that while no dramatic extension of life is imminent, the limits of human longevity remain an open scientific question — one likely to shape medicine, economics, and public policy in the 21st century.

What the Human Lifespans Research Found

Scientists analyzed extensive twin registry data collected across multiple countries over several decades. By comparing identical twins, who share nearly all genetic material, with fraternal twins, researchers could isolate inherited effects from environmental factors.

According to the study, lifespan variation attributable to genetics may exceed half of the total variation among individuals. Earlier estimates placed that figure much lower because deaths from accidents, infections, and other external causes blurred the biological signal.

Dr. Kaare Christensen, an aging researcher at the University of Southern Denmark and co-author of related longevity research, said the findings clarify a long-standing scientific question.

“When we remove early and preventable deaths from the data, the genetic component becomes much stronger,” Christensen explained in a research statement.

This shift does not mean lifestyle factors are unimportant. Rather, scientists say genetics defines biological potential while behavior determines whether individuals approach it.

The findings also suggest certain protective genes may regulate how cells repair damage, respond to inflammation, and resist age-related diseases. Those processes lie at the center of modern aging science.

Why Earlier Lifespan Estimates May Have Been Too Low

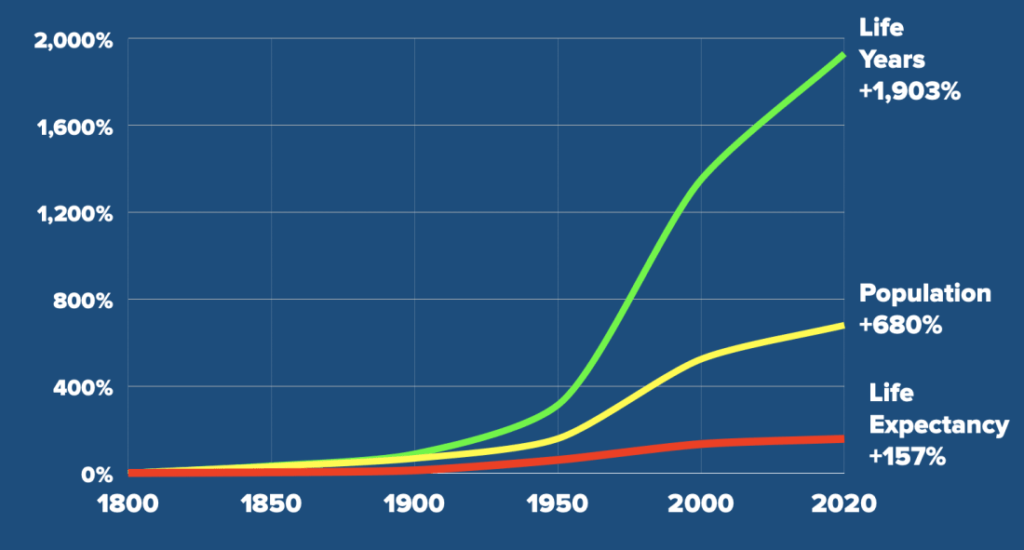

For most of human history, infectious disease, poor sanitation, and high infant mortality reduced average life expectancy. In the 19th century, global life expectancy was often below 40 years. Modern public health systems and antibiotics dramatically changed survival patterns.

Researchers argue older demographic statistics masked the species’ natural longevity.

In the past, many individuals died before age-related biological decline became the main cause of death. Today, chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders dominate mortality in developed countries.

That change makes it easier to observe aging itself rather than premature death. It also allows scientists to separate “life expectancy trends” from biological lifespan potential.

Longevity Research and the Debate Over Maximum Human Lifespan

The Human Lifespans findings have revived a major scientific debate: Is there a fixed human lifespan limit?

The verified longevity record remains 122 years, reached by French woman Jeanne Calment in 1997. Some demographers believe that age represents a biological ceiling. Others argue it reflects current medical limitations rather than human potential.

Biostatistician James Vaupel, former director of the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, long argued that longevity continues to expand gradually as healthcare improves.

Supporters of this view say survival rates among centenarians have steadily improved over decades. Critics note that gains slow sharply after age 110, suggesting biological constraints such as cellular deterioration and metabolic breakdown.

A growing field known as geroscience now studies whether aging itself can be treated medically rather than addressed disease by disease.

Aging Science: What Actually Causes Aging?

Scientists no longer describe aging simply as “wear and tear.” Modern aging science identifies several biological mechanisms:

Cellular Senescence

Old cells stop dividing but do not die. These cells release inflammatory signals that damage nearby tissue.

DNA Damage

Every day, human cells experience thousands of tiny DNA injuries. Repair systems weaken with age.

Telomere Shortening

Chromosomes have protective ends called telomeres. Each cell division shortens them. When they become too short, the cell stops functioning.

Mitochondrial Decline

Mitochondria produce energy for cells. Over time they generate harmful byproducts that accumulate damage.

Dr. Linda Partridge, a geneticist at University College London’s Institute of Healthy Ageing, explains:

“Aging is not a single process. It is a network of biological changes happening simultaneously.”

These processes influence cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes, and heart disease. As a result, slowing aging may reduce multiple illnesses at once.

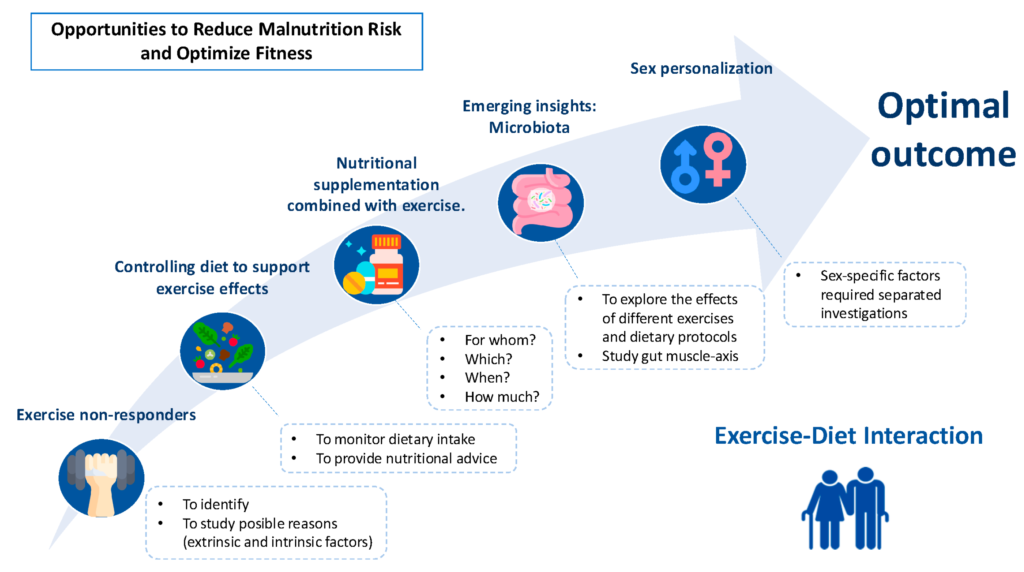

Lifestyle and Environment Still Matter

Even with strong genetic influence, daily habits still affect lifespan. Scientists consistently identify several factors associated with longer lives:

- Balanced nutrition

- Regular physical activity

- Low smoking rates

- Strong social connections

- Preventive healthcare

Partridge summarized the relationship between genetics and behavior:

“Genes load the gun, but environment pulls the trigger. Good lifestyle choices allow people to approach their biological potential.”

Research on so-called “Blue Zones” — regions with high numbers of centenarians such as Okinawa, Japan, and Sardinia, Italy — supports this conclusion. Residents often share plant-based diets, frequent walking, and strong community ties.

Medical Implications: Treating Aging Instead of Disease

The findings could influence future medicine. Instead of treating heart disease, cancer, and dementia separately, scientists hope to target aging itself.

Researchers are exploring therapies including:

- Drugs that remove senescent cells (senolytics)

- Metabolic regulators

- Anti-inflammatory compounds

- Stem-cell regeneration

- Gene-editing techniques

Some early clinical trials are already studying medications originally designed for diabetes and immune disorders to see whether they slow biological aging.

However, experts warn the goal is not immortality.

“The realistic objective is healthy aging,” said Partridge. “Adding healthy years matters more than adding years alone.”

Social and Economic Consequences

Longer Human Lifespans could reshape economies and social systems. Retirement ages, pension programs, and healthcare budgets depend heavily on demographic assumptions.

The United Nations projects the global population aged 65 and older will double by 2050. Some countries already face workforce shortages as populations age.

Economists suggest societies may adapt by:

- Raising retirement ages

- Encouraging lifelong education

- Expanding preventive healthcare

- Promoting flexible careers

Longer productive years could partially offset the costs of aging populations.

Ethical Questions and Inequality

The possibility of extending Human Lifespans also raises ethical concerns.

Experts warn longevity treatments may initially be expensive, potentially widening inequality between wealthy and poor populations. Access to advanced therapies could vary across countries.

Bioethicist Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel has argued societies must balance lifespan extension with quality of life and social equity.

Questions also arise about population growth, environmental sustainability, and resource distribution if humans routinely live much longer.

Scientific Uncertainty Remains

Despite growing evidence, researchers stress caution. Longevity studies depend on complex statistical modeling and incomplete historical records.

Many questions remain unresolved:

- Whether a fixed lifespan ceiling exists

- Whether medicine can slow aging significantly

- How genetic differences interact with modern lifestyles

Christensen summarized the scientific consensus cautiously:

“We are not proving humans will live to 150. We are showing the biological potential is higher than we once measured.”

FAQs About Human Lifespans May Be Longer Than Previously Estimated

Does the research mean people will suddenly live to 150?

No. The study indicates potential biological capacity, not immediate lifespan changes.

Are genes more important than lifestyle?

Both matter. Genetics sets the potential, while behavior influences outcomes.

What is the current confirmed maximum age?

122 years, verified through demographic records.

Will anti-aging medicine be available soon?

Scientists are researching therapies, but most remain experimental and years away from widespread use.