For NASA, delays are frustrating — but they are also part of doing human spaceflight safely. The agency’s upcoming Moon mission, Artemis II, was supposed to mark a historic moment: the first time astronauts travel beyond low-Earth orbit in more than half a century.

Instead, engineers recently discovered a technical issue serious enough to halt preparations and physically move the rocket off the launch pad. Rather than risk a crewed mission, NASA chose caution and ordered the giant Space Launch System rocket to be rolled back to its assembly building for repairs.

The decision highlights how complicated modern space missions are. A rocket is not simply fueled and launched; it is a delicate machine filled with pressurized gases, cryogenic fuel, sensors, and complex plumbing systems. A small abnormal reading can signal a serious malfunction once the vehicle is in space. In this case, a problem detected during testing revealed that a critical system inside the rocket was not functioning correctly, forcing engineers to pause the countdown long before liftoff.

The Artemis II launch delay became inevitable after engineers identified an interruption in helium flow within the rocket’s upper stage propulsion system. This component is essential because helium pressurizes fuel tanks and ensures propellant moves properly through the engines. Without stable pressurization, the rocket cannot safely perform the burn needed to send astronauts toward the Moon. NASA concluded that the only safe option was to roll the rocket back to the Vehicle Assembly Building so technicians could inspect, repair, and retest the affected hardware under controlled conditions.

Table of Contents

NASA Plans to Return the Artemis II Rocket

| Key Detail | Information |

|---|---|

| Mission Name | Artemis II |

| Rocket | Space Launch System (SLS) |

| Spacecraft | Orion crew capsule |

| Purpose | Crewed lunar flyby and systems testing |

| Issue Found | Interruption in helium flow in upper stage |

| Affected System | Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage |

| Required Action | Rollback to Vehicle Assembly Building |

| Original Launch Window | Early March 2026 |

| Current Status | Delayed pending repair and review |

| Importance | First human deep-space mission since 1972 |

What Went Wrong

The issue was detected during overnight testing and data analysis. Engineers observed irregular helium flow inside the rocket’s upper stage — a critical section responsible for pushing the Orion spacecraft from Earth orbit toward the Moon.

Helium plays a surprisingly important role in rocket operation. It is not a fuel. Instead, it acts as a pressurizing gas that pushes liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen through the propulsion system. Without correct pressure, the propellants cannot flow at the required rate, and the engines may lose power or shut down entirely.

In a crewed mission, even a minor fluctuation becomes unacceptable. During launch or a translunar injection burn, a pressurization failure could reduce engine thrust or destabilize the spacecraft’s trajectory. Because Artemis II carries astronauts, NASA cannot tolerate uncertainties. The abnormal readings suggested a valve, line, or regulator problem inside sealed hardware — equipment not easily accessible at the launch pad.

Why they Have to Haul the Rocket Back

Fixing a rocket on the launch pad sounds simple, but it is actually extremely difficult. The launch complex is designed for fueling and countdown operations, not major mechanical work. Many components are enclosed, pressurized, and protected by safety restrictions. Engineers cannot fully disassemble parts of the rocket outdoors.

Rolling the vehicle back to the Vehicle Assembly Building solves these problems. Inside the hangar-like structure, technicians can:

- open access panels safely

- inspect plumbing and valves

- replace defective components

- run controlled diagnostics

- perform verification tests

The building also protects the rocket from weather and allows specialized equipment to reach areas that would otherwise be inaccessible. For complex propulsion systems, detailed inspection often requires removing insulation and testing connections individually — tasks only possible indoors.

NASA has used rollbacks before. During earlier missions, similar procedures allowed engineers to fix leaks and instrumentation problems before launch. While it slows the schedule, it significantly reduces mission risk.

The Immediate Consequence

The most obvious result is a delay. The mission was targeting an early March 2026 launch window, but repairing and retesting the rocket means that timeline will shift.

A crewed mission requires far more verification than an uncrewed test flight. After repairs, NASA must repeat safety checks, analyze data, and conduct readiness reviews. Even after the rocket returns to the pad, the agency will still need a suitable launch window based on orbital alignment between Earth and the Moon.

In spaceflight, timing matters. Lunar missions depend on precise trajectories, and missing a launch opportunity can push a mission weeks or months into the future. Although frustrating, NASA prefers postponement over rushing a potentially unsafe launch.

What Artemis II actually is

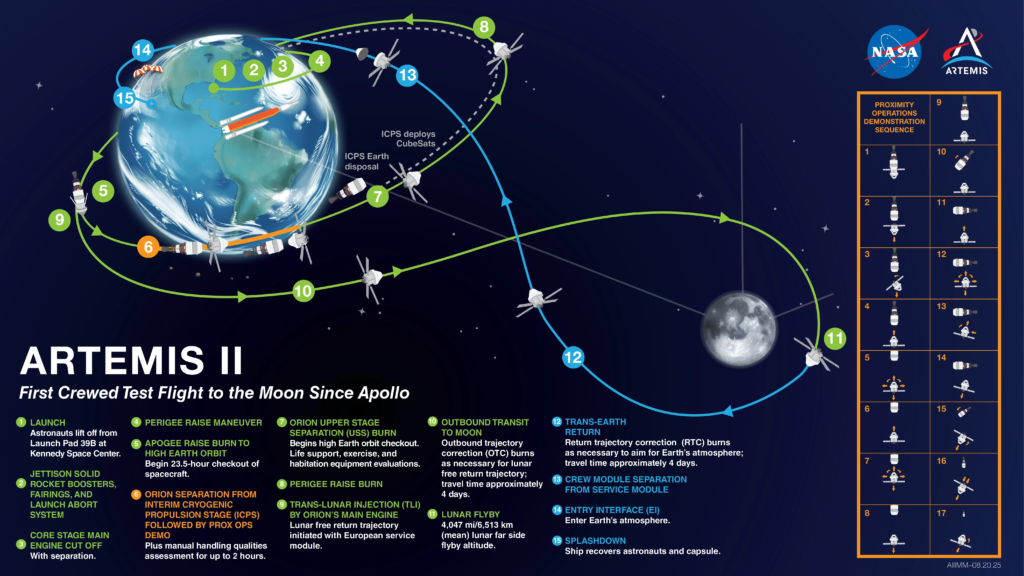

Artemis II is not a landing mission — but it is arguably just as important. The mission will send four astronauts around the Moon and back to Earth. It is designed to prove that the Orion spacecraft, life-support systems, and deep-space operations are safe for humans.

The astronauts will travel far beyond the International Space Station’s orbit. After launch, the rocket will place Orion into Earth orbit before firing the upper stage again to send the spacecraft toward the Moon. The crew will fly around the Moon and return home, testing navigation, communications, and onboard systems throughout the journey.

This will be the first human deep-space flight since the Apollo era ended in 1972. The mission acts as a rehearsal for Artemis III, which is intended to land astronauts on the lunar surface.

Why NASA Chose Safety over Schedule

To an outside observer, moving a rocket back into a hangar may seem dramatic. However, within the spaceflight community it is a normal — and responsible — decision.

Rocket failures often begin as small mechanical problems. A pressure irregularity, if ignored, can escalate into engine shutdown or loss of control during flight. Detecting the issue before launch is exactly what testing procedures are meant to do.

NASA’s approach reflects a long-standing principle: a delayed launch is acceptable, but a preventable accident is not. Human spaceflight demands extremely high reliability. Every system must perform perfectly in conditions where repair is impossible.

By rolling the rocket back, NASA gains time to understand the fault thoroughly. Engineers can fix not only the immediate issue but also verify that no related components are affected. This careful approach helps protect both astronauts and the future of the Artemis program.

Conclusion

The rollback of the Artemis II rocket represents a setback in schedule but a success in engineering vigilance. The detection of a helium flow problem showed that monitoring systems worked exactly as intended, identifying a risk before it became dangerous. Rather than pushing forward toward a deadline, NASA chose a safer path: repair, test, and confirm readiness.

The mission still carries enormous significance. When Artemis II finally launches, it will reopen deep-space travel for humans after more than fifty years. The temporary delay does not diminish that achievement — it strengthens it. Each additional inspection and test increases confidence that the astronauts aboard will travel safely to the Moon and back.

In space exploration, patience is not weakness. It is the price of reliability. The decision to haul the rocket back into the assembly building may have postponed liftoff, but it also ensured that when the countdown eventually reaches zero, the mission will be ready.