Plague-Era London Used Early Data Tracking: Plague-Era London Used Early Data Tracking to Understand the Outbreak and believe it or not, that 17th-century hustle laid the groundwork for how we handle public health crises today in the United States and across the globe. Long before spreadsheets, dashboards, or the CDC’s slick data trackers, Londoners were already counting deaths, studying patterns, and making decisions based on hard numbers. That’s right — they were working with early forms of what we now call public health surveillance. Now, I’ve spent years studying outbreak response systems and public health infrastructure, and here’s something folks don’t always realize: data saves lives. Whether we’re talking about the 1665 Great Plague or COVID-19, the core principle is the same — track it, understand it, respond to it. London’s early experiment with weekly death reporting wasn’t perfect, but it was a bold move in the right direction. And honestly? It was pretty ahead of its time.

Table of Contents

Plague-Era London Used Early Data Tracking

Plague-Era London Used Early Data Tracking to Understand the Outbreak, and that early commitment to counting, analyzing, and sharing mortality data shaped the very DNA of modern public health. What started as handwritten parish tallies evolved into the sophisticated epidemiological systems we rely on today in the United States. From a professional standpoint, the lesson is crystal clear: Data drives decisions. Whether in 1665 or 2025, communities that track trends and communicate transparently are better equipped to respond to crises. History isn’t just something we read about. It’s something we learn from — and sometimes, it’s surprisingly ahead of its time.

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| Historical Event | Great Plague of London (1665–1666) |

| Estimated Death Toll | Approx. 100,000 deaths (about 20% of London’s population) |

| Early Data Tool | Weekly Bills of Mortality |

| Data Collectors | Parish clerks and “searchers of the dead” |

| Modern Equivalent | CDC Mortality Surveillance System |

| Official Reference | CDC Data & Surveillance: https://www.cdc.gov/surveillance/index.html |

| Public Health Lesson | Transparent data influences behavior and policy |

| Career Insight | Epidemiologists & public health analysts use similar methods today |

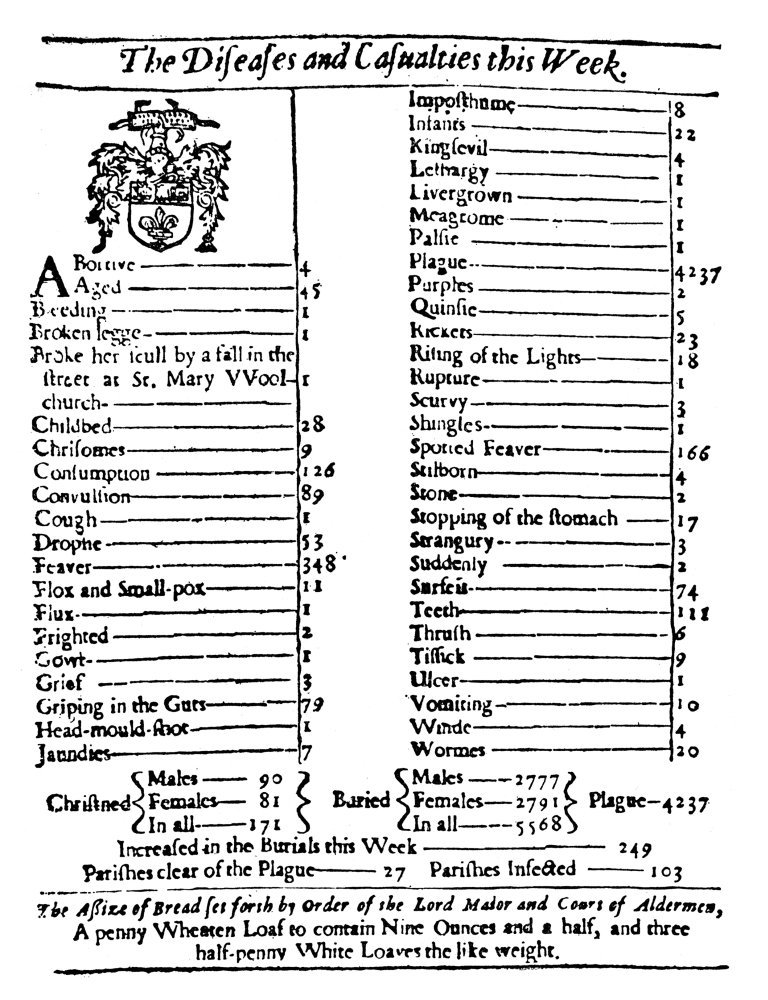

What Were the Bills of Mortality?

Let’s break it down real simple.

During the 1600s, London printed weekly reports called the Bills of Mortality. These documents listed how many people died and the causes of death — including deaths from the plague. The Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks gathered the data from each parish (think of it like neighborhoods).

Every week, these numbers were printed and sold publicly. People literally waited to see how bad things were getting. That’s early transparency in action.

Why It Mattered?

Those weekly numbers helped answer three big questions:

- Where is the disease spreading?

- Is it getting worse or better?

- Should we change our behavior?

Sound familiar? That’s exactly what we asked during COVID-19.

According to historians, about 100,000 people died during the Great Plague — roughly one in five Londoners. For comparison, the CDC reported over 1.1 million deaths in the U.S. from COVID-19 as of 2023.

Different centuries. Same need for reliable data.

Plague-Era London Used Early Data Tracking: How Data Was Collected in 1665?

Now here’s where it gets interesting.

The “Searchers of the Dead”

Women known as “searchers” examined bodies and determined causes of death. They weren’t doctors — medicine was still evolving — but they were trained observers. Parish clerks recorded their findings.

Was it perfect? Nope.

Some families reportedly bribed searchers to avoid labeling a death as “plague” because that would trigger quarantine measures. But even with imperfections, the system provided trend data — and trends are what matter in epidemiology.

Step-by-Step: How the System Worked

Step 1: A death occurred in a parish.

Step 2: A searcher identified a cause of death.

Step 3: Parish clerks compiled weekly totals.

Step 4: Bills were printed and distributed.

Step 5: Citizens and officials made decisions based on trends.

That’s basically an early public health dashboard — minus Wi-Fi.

How Plague-Era London Used Early Data Tracking Mirrors Modern U.S. Disease Tracking?

Today in America, we use advanced systems like:

- The CDC National Vital Statistics System

- State-level health department databases

- Electronic health records (EHRs)

- Real-time hospital reporting networks

The Core Principle Hasn’t Changed

Whether it’s plague in 1665 or influenza in 2025, we rely on:

- Consistent reporting

- Standardized categories

- Transparent communication

- Trend analysis

The difference? Technology.

Londoners used ink and paper. We use AI, modeling software, and cloud-based systems.

But at its heart, it’s the same strategy: Measure it so you can manage it.

The Power of Public Transparency

Here’s something professionals know well — but everyday folks sometimes overlook:

Public trust grows when data is shared openly.

When London printed weekly mortality reports, it created:

- Awareness

- Accountability

- Behavioral change

People left the city when numbers rose. Businesses closed. Travel slowed.

Fast-forward to today — when COVID case counts spiked, Americans:

- Masked up

- Avoided gatherings

- Switched to remote work

The World Health Organization emphasizes the importance of transparent reporting in outbreak control.

Transparency isn’t just ethical. It’s strategic.

Professional Insights: What Modern Epidemiologists Can Learn

As someone who’s worked alongside public health teams, I can tell you — historical data systems matter.

Here are three lessons professionals still apply:

1. Early Reporting Saves Time

The sooner you identify a spike, the faster interventions can begin.

In 1665, when plague deaths jumped sharply in specific parishes, authorities imposed quarantines. Today, rapid detection systems do the same thing.

2. Local Data Is Gold

Parish-level reporting allowed targeted response.

In the U.S., county-level data helps deploy resources where needed most. The CDC and state health departments rely heavily on localized reporting.

3. Imperfect Data Is Better Than No Data

Even if the Bills of Mortality weren’t 100% accurate, they revealed patterns. Epidemiology isn’t about perfection — it’s about probability and trend recognition.

Why Plague-Era London Used Early Data Tracking Matters for Careers Today?

If you’re a student, professional, or career-switcher looking into public health — this history shows the foundation of the field.

In-Demand Careers Inspired by Early Data Tracking

- Epidemiologist (Median U.S. salary: ~$78,000 per year — Bureau of Labor Statistics)

- Biostatistician

- Public Health Analyst

- Data Scientist (Healthcare Focus)

- Health Policy Advisor

Data-driven outbreak response is not going anywhere. If anything, it’s expanding.

Practical Advice: How Communities Can Apply These Lessons Today

Even outside government systems, communities and organizations can use similar principles.

Easy Action Steps

1. Track Trends, Not Just Events

If you’re running a school or business, monitor absentee rates. A spike might indicate illness spread.

2. Communicate Clearly

Share updates regularly. Even simple weekly emails build trust.

3. Use Official Sources

Rely on CDC and state health departments rather than social media rumors.

4. Educate Early

Understanding data basics empowers families and employees to make smart decisions.

Remember — data is not about fear. It’s about preparation.

Comparing 1665 Plague Data to COVID-19 Dashboards

Let’s put it side by side:

| 1665 London | 2020 USA |

|---|---|

| Weekly printed sheets | Real-time digital dashboards |

| Parish-level counts | County and state-level reporting |

| Manual recordkeeping | Automated electronic systems |

| Physical distribution | Online access & media briefings |

Different tools. Same concept.

And here’s the real kicker: London’s approach helped inspire later statistical advancements, including the work of early demographers like John Graunt, who analyzed mortality patterns and laid groundwork for modern statistics.

Solar Panel Farming Study Finds Changes in Crop Yield and Costs

Study Finds Kimchi Supports the Immune System Without Over activating It

10 Human Evolution Discoveries From 2025 That Changed What We Know