New analysis of Pompeii Victims’ Wool garments is prompting historians and archaeologists to reconsider when Mount Vesuvius destroyed the Roman city in AD 79. Researchers say the heavy clothing worn by victims, along with seasonal food remains and inscriptions, strongly suggests the eruption occurred in autumn rather than the traditionally accepted August date.

Table of Contents

Pompeii Victims’ Wool Clothing

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Traditional date | August 24, AD 79 |

| New clothing evidence | Victims wore layered wool garments |

| Seasonal clues | Autumn fruits, sealed wine jars, October inscription |

Why the Pompeii Victims’ Wool Evidence Is Being Questioned

For centuries, the destruction of Pompeii was dated to late summer based on written testimony from Roman author Pliny the Younger, who witnessed the disaster across the Bay of Naples.

His letters describe a massive cloud rising from Mount Vesuvius, falling ash, and darkness at midday. The account remains one of the earliest scientific observations of a volcanic eruption.

However, archaeological discoveries are increasingly challenging that timeline.

Excavations have revealed that many victims wore thick wool cloaks and tunics. In the Mediterranean climate, such clothing is typically associated with cooler temperatures.

Gabriel Zuchtriegel, director of the Pompeii Archaeological Park, said the garments “are consistent with colder seasonal conditions and should be interpreted alongside other environmental evidence.”

The Pompeii Victims’ Wool findings therefore do not stand alone. Instead, they support multiple independent indicators suggesting a later date.

Archaeological Evidence Supporting an Autumn Date

Seasonal Foods and Agriculture

Archaeologists uncovered food products inconsistent with an August environment. Among the remains were chestnuts, walnuts, olives, and pomegranates — crops harvested in early autumn.

Large clay containers called dolia were sealed with lids. These vessels were used to store wine after the grape harvest, which typically occurred in September and October in Roman Campania.

This is important because the city appears to have been operating normally. Shops were stocked. Bakeries were open. Bread loaves were still inside ovens.

The findings indicate daily commerce was continuing immediately before the disaster.

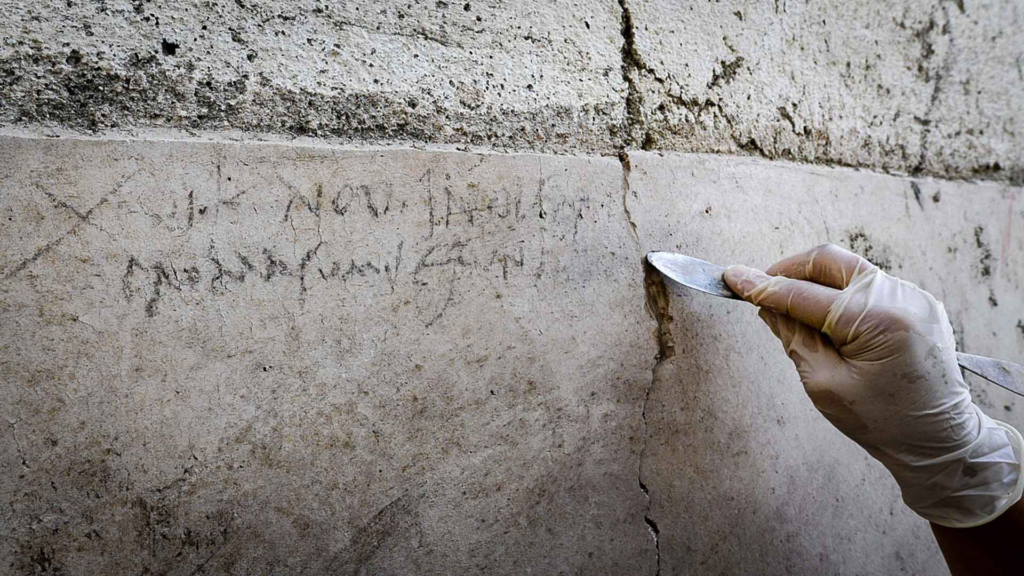

The Charcoal Inscription

One of the strongest clues appeared in 2018. Archaeologists found a charcoal writing on a wall referencing a date equivalent to October 17.

Unlike carved inscriptions, charcoal markings deteriorate quickly. Experts believe the message was written only days before the eruption.

The Italian Ministry of Culture described the discovery as “a decisive chronological indicator.”

The Role of Clothing in Reconstructing Ancient Disasters

Clothing offers environmental context. Textile remains act as indirect climate data.

Roman society primarily used wool, but layering multiple garments indicates colder weather. Southern Italy’s August temperatures often exceed 30°C (86°F). Thick cloaks would have been uncomfortable in such heat.

Some victims also carried braziers — portable heaters — suggesting falling temperatures and ash-darkened skies.

The Pompeii Victims’ Wool therefore functions as a behavioral clue. People dressed for cool conditions, not summer heat.

What the Eruption Was Actually Like

The Mount Vesuvius eruption was not a single explosion. It occurred in stages over roughly 18 to 24 hours.

First, pumice stones fell from the sky. Roofs collapsed under weight. Many residents initially survived.

Later came pyroclastic flows — superheated gas and ash moving faster than a hurricane. Temperatures exceeded 400°C (752°F). These flows killed remaining inhabitants instantly.

Volcanologists today classify this type of event as a Plinian eruption, named after Pliny the Younger’s observations.

Scientists studying ash layers have reconstructed a timeline:

- Ash fall phase

- Structural collapses

- Toxic gases

- Pyroclastic surge

Most victims died during the final phase.

Why the Traditional Date Persisted

The August date comes from medieval copies of Pliny’s letters. Ancient manuscripts were copied by hand for centuries.

Even small copying errors could change calendar dates. Roman calendars also differed from modern ones.

Classical scholars believe scribes may have misinterpreted Roman numerals or abbreviated month names.

This is not unusual. Many ancient texts exist only through later reproductions.

Eyewitness Account: Pliny the Younger

Pliny’s description remains crucial to understanding the disaster. He wrote:

A cloud appeared “like an umbrella pine tree,” rising high and spreading branches.

He also described people covering their heads with pillows to protect themselves from falling debris.

Across the bay, he experienced earthquakes, darkness, and ash accumulation.

His account also confirms panic, evacuation attempts, and confusion about the nature of the event.

Romans did not understand volcanoes scientifically. Many believed the eruption was a supernatural omen.

Not All Experts Agree

Some scholars caution against overinterpreting the clothing evidence.

Wool was widely used year-round in Roman daily life. Citizens may have worn cloaks while fleeing sharp pumice stones.

Others argue volcanic ash clouds may have lowered temperatures dramatically during the event itself.

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, former director of the Herculaneum Conservation Project, has said physical and textual evidence should be considered together rather than separately.

The debate remains open within the academic community.

What Pompeii Reveals About Roman Daily Life

Pompeii offers an unparalleled snapshot of Roman daily life.

The city contained:

- restaurants (thermopolia)

- bathhouses

- taverns

- apartment blocks

- luxury villas

Graffiti on walls revealed political opinions, advertisements, and even jokes.

One inscription advertised gladiator fights. Another declared romantic affection.

Because ash preserved organic materials, archaeologists recovered bread, fruit, wooden furniture, and even pets.

Pompeii is therefore not only a disaster site but a preserved living city.

The Science Behind Archaeological Evidence Pompeii

Modern science has transformed excavation methods.

Researchers now use:

- DNA testing

- isotopic analysis

- 3D scanning

- forensic anthropology

Recent studies show victims were not all wealthy Romans, as once thought. Many were enslaved individuals and workers.

Isotope analysis of teeth revealed diets rich in grain and fish sauce known as garum.

3D reconstructions have even recreated victims’ faces using skull measurements.

These advances help historians move beyond dramatic stories and toward accurate social history.

Why the Pompeii Victims’ Wool Discovery Matters Today

The significance goes beyond ancient history.

Volcanologists study Pompeii to improve disaster response planning. Cities near volcanoes today — including Naples, home to more than 3 million people — face similar risks.

Understanding human behavior before evacuation helps authorities design warning systems.

Modern monitoring at Mount Vesuvius now includes:

- seismic sensors

- gas emission detectors

- satellite deformation measurements

Authorities maintain evacuation plans for surrounding communities.

Pompeii, therefore, informs modern emergency management.

What Happens Next

Excavations continue in northern Pompeii, where nearly one-third of the ancient city remains buried.

Each discovery refines the timeline of the Mount Vesuvius eruption.

Zuchtriegel said the city “continues to provide new historical data each year,” emphasizing ongoing research rather than a completed story.

The precise day of the disaster may never be known with absolute certainty. But the Pompeii Victims’ Wool evidence is steadily shifting scholarly opinion toward an autumn catastrophe.

FAQs About Pompeii Victims’ Wool Clothing

What is the traditional eruption date?

August 24, AD 79.

What evidence suggests autumn?

Wool clothing, autumn crops, sealed wine jars, and a charcoal inscription dated October.

How many people died?

Approximately 2,000 bodies have been found, though the population may have been closer to 10,000–15,000.

Did anyone survive?

Yes. Many residents fled during the early ash fall stage.