Archaeologists in eastern Scotland say newly unearthed Roman Altars near Edinburgh provide strong evidence that the Roman Empire maintained an organized military and religious presence beyond its traditionally recognized frontier. The second-century monuments were discovered at a Roman fort site and date to a brief northern expansion during the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius, offering new insight into life along the empire’s shifting borderlands.

Table of Contents

Roman Altars

| Key Fact | Detail |

|---|---|

| Location | Inveresk, East Lothian, Scotland |

| Date | Around AD 140 |

| Religious Dedication | Mithras, a soldiers’ mystery religion |

Excavations continue at the Inveresk site, and archaeologists believe additional discoveries may further clarify Roman intentions in Scotland. “Each artifact adds detail,” Hunter said. “The Roman frontier was never a simple line on a map.”

What Was Found

Researchers uncovered two carved stone Roman Altars at a Roman military fort in Inveresk, east of modern Edinburgh. The stones contain inscriptions dedicated to Mithras, a deity worshipped in a secretive religious tradition practiced primarily by Roman soldiers.

Experts from National Museums Scotland dated the carvings to about AD 140, when Emperor Antoninus Pius expanded Roman operations northward into southern Scotland.

“These monuments were commissioned by soldiers themselves,” said Dr. Fraser Hunter, principal curator of prehistoric and Roman archaeology at National Museums Scotland. “They reflect personal belief and military community life.”

The carvings include decorative borders and a Latin dedication. Such features indicate skilled craftsmen were present locally, suggesting the garrison was not a temporary encampment but a functioning settlement.

Why the Discovery Matters

The importance of the Roman Altars lies in what they imply. Religious monuments generally appear only where troops stay for extended periods.

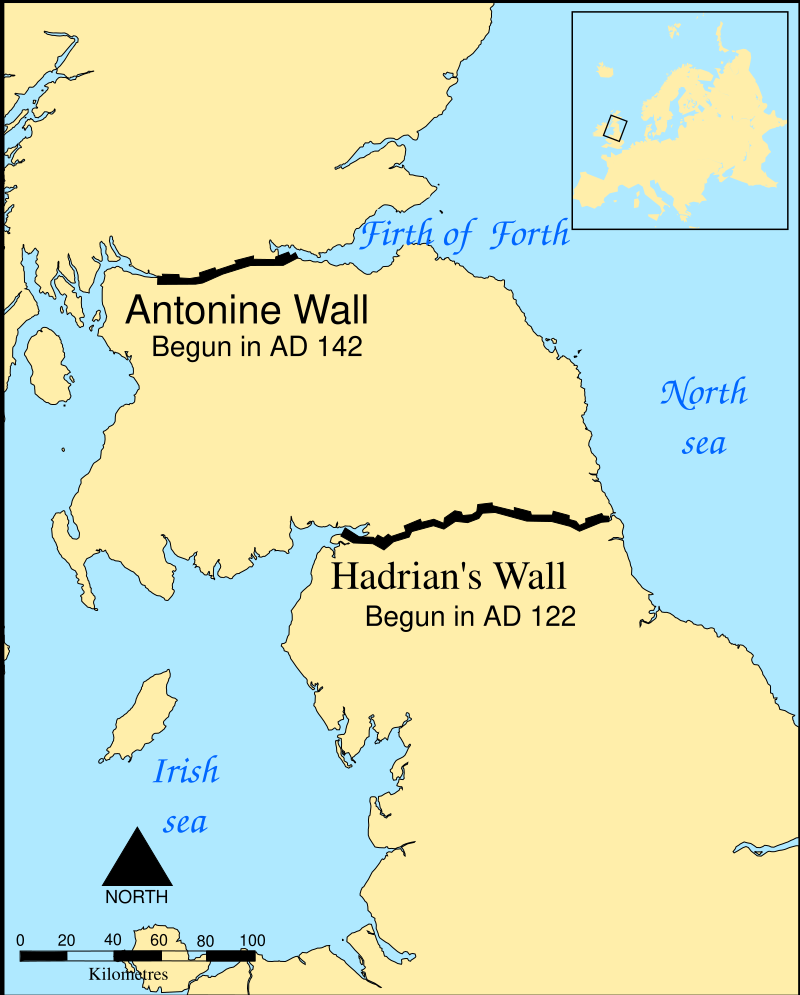

For decades, the Roman Empire’s northern boundary in Britain was thought to be Hadrian’s Wall, built around AD 122 across northern England. However, these altars date to a later expansion during which Roman forces advanced to the Antonine Wall, about 160 kilometers farther north.

Roman Frontier Britain Was Mobile

Historians now emphasize that Roman frontiers were flexible zones rather than permanent borders.

“Rome did not see borders the way modern nations do,” said Dr. Rebecca Jones, a Roman historian at the University of Glasgow. “The frontier shifted depending on military strategy, diplomacy, and supply capacity.”

The altars confirm that Roman soldiers were stationed long enough to establish religious customs and communal identity. This implies administration, supply networks, and command structure existed in southern Scotland.

The Soldiers Behind the Stones

Roman armies were multinational institutions. Auxiliary units were recruited from across the empire, including Syria, Germany, Spain, and North Africa.

These troops often served far from their homelands. Archaeological records from Roman Britain reveal inscriptions written by soldiers born thousands of miles away.

The Mithras cult was particularly associated with the military. Worship occurred in small temple chambers, often underground or windowless, symbolizing caves linked to the myth of the god Mithras slaying a sacred bull.

Historians believe the religion appealed to soldiers because it emphasized loyalty, rank, and initiation ceremonies.

“The army created a shared identity among men from different cultures,” explained David Breeze, former chief inspector of ancient monuments for Historic Scotland. “Religious practice helped maintain cohesion in isolated frontier environments.”

Daily Life at the Frontier

The Roman Altars also open a window into daily life at a remote garrison.

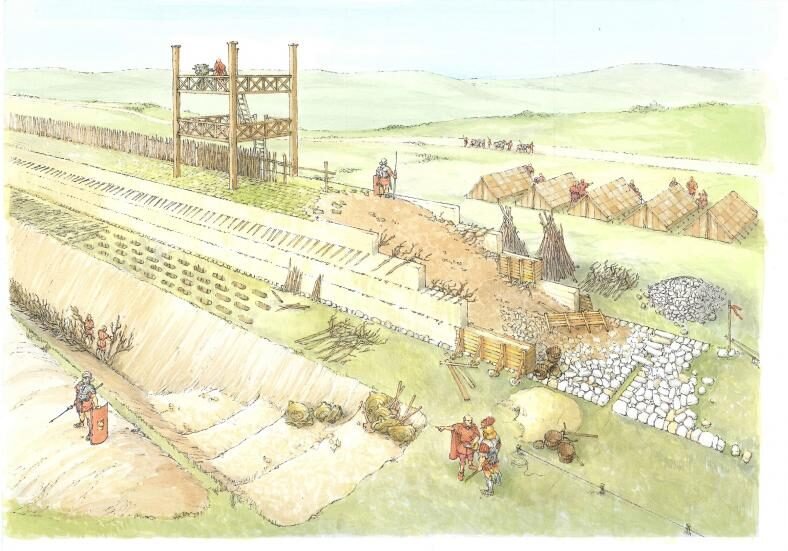

A typical Roman frontier fort housed roughly 500 to 1,000 troops. Surrounding the fort was a civilian settlement known as a vicus. Traders, blacksmiths, families, and merchants lived there.

Archaeological excavations at other Roman forts in Britain have revealed:

- bakeries producing bread for troops

- bathhouses with heated floors

- hospitals with surgical instruments

- taverns and shops selling imported goods

Food remains show soldiers ate beef, pork, barley, wheat, and imported wine and olive oil. These supplies required complex logistics. Goods arrived by sea, river, and road from southern Britain and continental Europe.

The presence of Roman Altars indicates such infrastructure likely existed at Inveresk as well.

Dating the Occupation

The Roman occupation of the Antonine frontier lasted approximately from AD 142 to AD 165. Afterward, troops withdrew south to Hadrian’s Wall.

Historians cite several reasons for the retreat:

- difficult terrain and climate

- extended supply routes

- pressure from local tribes

- shifting priorities elsewhere in the empire

Maintaining troops in northern Britain was expensive and strategically uncertain. The empire instead consolidated its defenses at the more stable Hadrianic frontier.

Religion as Evidence of Control

Military structures alone do not prove occupation. Religious practice does.

When soldiers establish temples and dedicate Roman Altars, they signal permanence and confidence in their position.

Archaeologists interpret religious dedication as a psychological commitment to place. Soldiers expected to remain long enough to invest in ritual life.

The discovery therefore changes the interpretation of Roman expansion into Scotland. It suggests an attempt to integrate territory rather than merely patrol it.

Interaction With Local Populations

The frontier was not simply a military barrier. It was also a contact zone.

Roman soldiers traded with local Celtic tribes. Archaeological finds across Scotland include Roman coins, pottery, and jewelry far beyond the walls.

Some historians believe peaceful exchange was as important as warfare.

“Frontiers were places of negotiation,” said Dr. Simon Elliott, a Roman military historian. “Trade, diplomacy, and alliances shaped Rome’s control more than battles alone.”

Local leaders sometimes cooperated with Rome for economic benefits. In return, Rome gained intelligence and stability.

Broader Historical Context

The Roman Empire invaded Britain in AD 43 under Emperor Claudius. Over the next century, Roman administration transformed much of England and Wales through roads, towns, taxation systems, and legal governance.

However, Scotland remained contested territory.

The Antonine Wall represented Rome’s most ambitious northern expansion. Constructed largely of turf with a deep defensive ditch, it required constant manpower.

More than 16 forts lined the wall. Roads connected them, allowing rapid troop movement. Signal towers communicated warnings across long distances.

The newly discovered Roman Altars support the interpretation that Rome briefly treated southern Scotland as part of its province.

What Experts Are Saying

Scholars say the discovery may change how Roman Britain is taught.

“For generations, the public learned Rome stopped at Hadrian’s Wall,” Jones said. “Now we see a deeper, more complicated occupation.”

Archaeologists also emphasize cultural diversity within the Roman military. Soldiers stationed in Scotland likely spoke multiple languages and practiced varied traditions.

The Roman Altars demonstrate shared belief despite those differences.

Archaeological Methods Used

Modern archaeology played a crucial role in identifying the altars’ significance.

Researchers used:

- stratigraphy to date soil layers

- epigraphy to interpret Latin inscriptions

- comparative artifact analysis with other Roman sites

- material composition studies to identify stone origin

Preliminary analysis suggests the stone may have been quarried locally, indicating the Romans used regional resources rather than importing materials from England.

What Happens Next

The altars are undergoing conservation to prevent erosion and preserve inscriptions. Once stabilized, they will go on public display.

Further excavation may reveal a temple building or additional artifacts such as coins, tools, or personal objects.

Researchers hope to identify the specific military unit stationed at the fort.

FAQ

Did Rome permanently conquer Scotland?

No. Rome occupied parts of southern Scotland for roughly two decades before withdrawing.

Why are Roman Altars important?

They show long-term settlement and religious life rather than temporary military presence.

Who worshipped Mithras?

Mostly Roman soldiers stationed at frontier forts.

Why did the Romans leave?

The cost of defending remote territory exceeded its strategic value.