A 7-Foot “Giant” discovered within a Viking Age mass grave near Cambridge, England, has provided archaeologists with rare evidence of early medieval violence and medical practice. The burial pit, dating to roughly the late 8th or 9th century, contained multiple young men, including an exceptionally tall individual who survived a surgical procedure on his skull more than 1,100 years ago.

Table of Contents

7-Foot “Giant”

| Key Fact | Detail/Statistic |

|---|---|

| Location | Wandlebury Country Park, near Cambridge |

| Date | About 772–891 AD |

| Unique discovery | Tall man survived cranial surgery |

What the Viking Age Mass Grave Shows

The burial site lies inside Wandlebury Ring, an ancient hillfort in eastern England that had been used since the Iron Age. Archaeologists initially expected to find routine medieval burials but instead uncovered a pit containing commingled bones.

The grave held disarticulated skeletons — skulls separated from bodies, limbs placed apart, and incomplete remains. The absence of coffins, shrouds, or grave goods contrasts sharply with typical Christian burials of the era.

Dr. Corinne Duhig, a biological anthropologist involved with the excavation, stated in a university briefing that the pattern suggests “a group disposed of quickly after death rather than buried with ritual care.”

The remains indicate several individuals died violently at approximately the same time.

Evidence of Execution During Viking-Saxon Conflict

Between 790 and 900 AD, England experienced repeated Viking raids. Historical records describe coastal attacks, plundered monasteries, and captured prisoners.

The Wandlebury burial fits this turbulent historical backdrop.

Many skeletons show cut marks consistent with weapons such as swords or axes. Several skulls display sharp-force trauma, suggesting execution rather than battlefield combat. In some cases, neck vertebrae injuries indicate beheading.

Historians say public execution was not uncommon in medieval Europe. Authorities sometimes displayed body parts to warn others against rebellion or crime.

Archaeologists suspect the individuals may have been raiders captured by local authorities or, alternatively, mercenaries or criminals punished by Anglo-Saxon rulers. At present, scientists have not reached a final conclusion.

The So-Called 7-Foot “Giant”

One skeleton quickly stood apart.

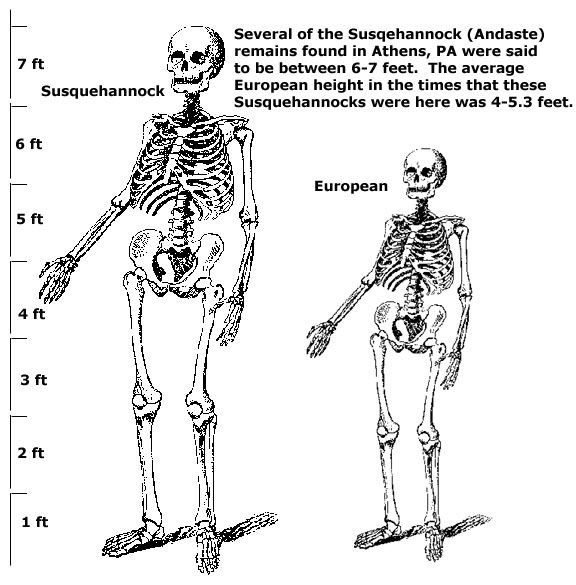

The man measured about 1.95 meters (6 feet 5 inches), far taller than the typical adult male in early medieval England. Modern observers describe him as a 7-Foot “Giant”, but experts emphasize he was not mythical.

Average height during the period ranged from 5 feet 5 inches to 5 feet 7 inches. A man of his size would have been immediately recognizable.

Researchers believe the height resulted from pituitary gigantism, a condition caused by excessive growth hormone production, often linked to a tumor affecting the pituitary gland.

Such individuals may experience joint pain, headaches, vision problems, and neurological symptoms.

The skeleton also showed abnormal bone thickness and joint wear, supporting the medical explanation.

Evidence of Ancient Brain Surgery (Trepanation)

The most significant discovery lies in the skull.

A carefully cut circular hole about 3 centimeters wide appears on the cranium. The surrounding bone healed, proving the man lived long after the operation.

This procedure — trepanation — involves drilling or scraping a hole into the skull to relieve pressure or treat neurological illness.

Researchers believe the operation may have attempted to relieve symptoms caused by a tumor or head trauma.

Despite the lack of modern anesthesia or antiseptics, ancient surgeons sometimes succeeded. They likely used metal blades and herbal remedies to limit infection.

Healing patterns show bone regrowth, meaning the patient survived weeks, months, or possibly years after surgery.

How Medieval Surgeons Could Perform the Operation

Historians and medical researchers have studied trepanation across ancient cultures. Practitioners probably followed a careful method:

- Shaving the scalp

- Marking the surgical location

- Scraping or drilling the skull gradually

- Avoiding the brain membrane

- Applying plant-based antiseptics such as honey or herbal pastes

Remarkably, survival rates in some ancient societies exceeded 50 percent according to skeletal evidence. The Wandlebury case suggests early English practitioners had practical anatomical knowledge gained through observation and experience.

Why the Discovery Matters

The burial site helps scholars understand daily realities of early medieval life.

1. Violence and Justice

The remains demonstrate organized punishment or warfare during the Viking period. Written chronicles often exaggerate events; physical evidence confirms real violence.

2. Medical Knowledge

The successful surgery indicates practitioners recognized head trauma and attempted treatment rather than fatalistic acceptance of illness.

3. Social Care

The tall man likely needed help during recovery. Someone fed him, protected him, and monitored healing, suggesting community support networks existed.

Daily Life Around the Time of the 7-Foot “Giant”

During the late 8th and 9th centuries, England was divided into Anglo-Saxon kingdoms such as Mercia, Wessex, and East Anglia.

Communities were rural and agricultural. Most people farmed grain, raised animals, and lived in wooden houses with thatched roofs. Medical care depended on local healers, monks, or experienced individuals rather than trained physicians.

Illnesses included infections, injuries from manual labor, and warfare wounds. Herbal medicine was common. Treatments used plants like willow bark for pain and garlic for infection.

The survival of the 7-Foot “Giant” after surgery suggests a healer with unusual skill operated in the region.

Context: Trepanation in Human History

Trepanation predates written history. Archaeologists have found examples in:

- Neolithic France

- Ancient Peru

- Central Asia

- Africa

In South America, some Inca skulls show multiple healed procedures, meaning patients survived several operations.

The Wandlebury example is among the clearest early medieval British cases.

Scientific Testing and Future Research

Researchers are now performing advanced laboratory tests.

Isotope Analysis

Chemical signatures in teeth and bones reveal where a person grew up by comparing local water and soil composition.

DNA Testing

Ancient DNA may show whether the men were Scandinavian migrants or local inhabitants.

Pathology Studies

Scientists will analyze diet, disease, and trauma patterns.

These methods could determine whether the individuals were invaders, prisoners, or local people punished by authorities.

Broader Historical Significance

The discovery reshapes common perceptions of the Viking Age.

Popular culture often depicts Vikings as the sole aggressors. However, archaeological evidence shows violence occurred on multiple sides. Communities defended territory, punished criminals, and fought internal conflicts.

The burial pit provides a physical narrative beyond written chronicles.

Ethical Considerations in Archaeology

Modern archaeologists treat human remains with strict ethical standards.

After study, remains are typically reburied or stored respectfully in research institutions. Specialists consult local authorities and sometimes religious representatives.

The excavation team says all analysis aims to better understand history rather than sensationalize death.

Conclusion

The 7-Foot “Giant” within the Viking Age mass grave offers an extraordinary intersection of archaeology, medicine, and history. The evidence reveals a violent period but also shows compassion and medical effort in early medieval society. As scientific testing continues, researchers hope to identify who these men were and how their lives ended — and how one unusually tall individual survived surgery centuries before modern medicine.

FAQ

Was he truly 7 feet tall?

No. He was approximately 6 feet 5 inches. The description reflects modern fascination, not literal measurement.

How did he survive surgery without anesthesia?

Pain management likely involved alcohol, herbal sedatives, and restraint. Infection prevention may have relied on honey or plant antiseptics.

Were Vikings responsible?

Possibly, but scientists have not confirmed. The dead could be raiders, locals, or prisoners.

Why is this discovery important?

It provides physical proof of early medical treatment and violence during the Viking Age.