As the largest generation in U.S. history moves deeper into retirement, anxiety over the future of Social Security is rising among Baby Boomers. Long-standing funding challenges, political deadlock, demographic shifts, and rising living costs are converging at a moment when millions of older Americans depend on the program as their primary source of income.

Table of Contents

A Retirement Wave Unlike Any Before

Baby Boomers, born between 1946 and 1964, represent a demographic force unmatched in U.S. history. Roughly 73 million Americans fall into this cohort, and the pace at which they are entering retirement is reshaping the nation’s economic and social landscape.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, about 10,000 Americans reach age 65 each day, a trend that began in 2011 and will continue through the end of the decade. The scale and speed of this transition have intensified scrutiny of Social Security, the federal program designed to provide a basic income floor for retirees.

Social Security was never intended to serve as the sole source of retirement income. Yet for many Boomers, particularly those with modest lifetime earnings, it has become exactly that.

How Social Security Was Designed—and Why That Matters Now

When Social Security was established in 1935, average life expectancy at birth in the United States was about 61 years. The program assumed that most beneficiaries would collect payments for a relatively short period.

Today, average life expectancy exceeds 76 years, and many retirees spend two or three decades drawing benefits. At the same time, birth rates have declined steadily, reducing the number of workers paying payroll taxes to support each retiree.

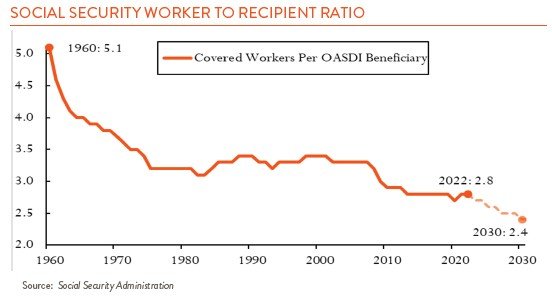

In 1960, there were roughly five workers for every Social Security beneficiary. Today, that ratio has fallen to about 2.8 and is projected to decline further, according to Social Security Administration data.

“This is the central challenge facing the program,” said Alicia Munnell, director of the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. “The math has changed, but the financing structure largely has not.”

Trust Fund Projections Fuel Public Concern

The most visible source of anxiety is the projected depletion of the Social Security retirement trust fund. According to the program’s trustees, reserves could be exhausted by the mid-2030s if Congress does not act.

Trust fund depletion does not mean the program would collapse. Payroll taxes would continue to flow in, covering roughly 75 percent of scheduled benefits. However, that shortfall would trigger automatic benefit reductions unless lawmakers intervene.

For retirees already living on fixed incomes, even partial cuts are alarming. “A 20 or 25 percent reduction is not something most retirees can absorb,” said Kathleen Romig, a senior policy analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “Especially not when healthcare and housing costs are rising.”

Social Security’s Outsized Role in Boomer Finances

Social Security plays a far larger role in retirement security than many Americans realize. According to federal data, about 40 percent of people aged 65 and older rely on Social Security for at least half of their income. Roughly 20 percent depend on it for nearly all of their income.

That reliance is particularly strong among lower-income households, women, and people of color, who often faced wage gaps and intermittent work histories over their lifetimes.

The erosion of traditional pensions has further increased dependence on Social Security. While earlier generations commonly retired with guaranteed employer pensions, most Boomers spent their working years shifting toward defined-contribution plans such as 401(k)s.

Those plans require consistent contributions, market discipline, and financial literacy—factors that varied widely across the workforce.

Inflation and Cost Pressures Intensify Anxiety

Recent economic conditions have sharpened concerns. Although inflation has moderated from its peak, prices for essentials such as housing, food, and healthcare remain significantly higher than they were before the pandemic.

Healthcare costs pose a particular challenge. Medicare covers many services, but out-of-pocket expenses for premiums, prescription drugs, dental care, and long-term care can consume a substantial share of retirement income.

According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, healthcare spending grows faster than inflation overall, a trend expected to continue as the population ages.

“Social Security benefits are indexed to inflation, but that adjustment often lags real-world expenses,” said Romig. “Many retirees feel they are constantly trying to catch up.”

Political Gridlock and Competing Reform Visions

Despite broad agreement among economists that Social Security’s challenges are manageable, political consensus has proved difficult.

Some lawmakers favor increasing payroll taxes, particularly by raising or eliminating the income cap above which earnings are not taxed for Social Security. Others argue for slowing benefit growth or raising the full retirement age to reflect longer life expectancies.

Each approach carries trade-offs, and advocacy groups warn that certain reforms could disproportionately affect lower-income workers or those in physically demanding jobs.

“People hear proposals floated without knowing which ones will stick,” said Nancy LeaMond, executive vice president of AARP. “That uncertainty feeds fear.”

Behavioral Shifts Among Baby Boomers

The uncertainty surrounding Social Security is already shaping behavior. Some Boomers are choosing to claim benefits earlier than planned, worried that future changes could reduce payouts.

Others are delaying retirement or returning to the workforce, either full-time or part-time, to supplement their income. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, labor force participation among adults aged 65 and older has risen steadily over the past two decades.

Financial planners say these decisions can carry long-term consequences. Claiming early locks in lower monthly benefits for life, while working longer may improve financial resilience but is not an option for everyone.

Uneven Impact Across Regions and Communities

Concerns about Social Security are not evenly distributed. Retirees in high-cost metropolitan areas face greater pressure than those in regions with lower housing and healthcare costs.

Rural retirees may face different challenges, including limited access to healthcare providers and fewer job opportunities if they seek to work longer.

“These anxieties are deeply shaped by where people live and what resources they have,” said Munnell. “There is no single Boomer experience.”

How Boomers Compare With Younger Generations

While Baby Boomers worry about benefit reductions, younger generations express concern about whether Social Security will be there at all. Surveys by the Pew Research Center show that many Millennials and Gen Z workers doubt they will receive benefits comparable to those of current retirees.

That generational tension complicates reform efforts. Policymakers must balance protecting current beneficiaries with maintaining confidence among future contributors.

“The political risk is that delay makes the problem harder and the solutions more painful,” said Romig.

What Experts Say About the Path Forward

Most analysts agree that the sooner Congress acts, the more gradual and less disruptive the changes can be. Options include modest tax increases phased in over time, incremental benefit adjustments, or a combination of both.

Historically, Social Security reforms have been bipartisan, most notably in 1983, when lawmakers acted to shore up the program amid a funding crisis.

“There is no technical barrier to fixing Social Security,” said Munnell. “The barrier is political will.”

Looking Ahead

For now, Social Security continues to pay full benefits, and no immediate changes are scheduled. But as Baby Boomers age, their growing unease reflects a broader national reckoning with how the United States supports retirement in an aging society.

Whether lawmakers act sooner or later will shape not only the future of the program, but also the sense of security felt by millions who depend on it.

FAQ

Will Social Security run out of money?

No. Payroll taxes would still fund most benefits even if trust fund reserves are depleted.

Why are Baby Boomers particularly concerned?

Most are already retired or close to retirement and have limited ability to offset benefit reductions.

Can the program be fixed?

Yes. Experts agree that policy options exist, but political agreement is required.